NOVEMBER NOSTALGIA

THIS MONTH’S BOOK SPECIALS

Before turning to the ruminations that form a regular part of this monthly newsletter, let me begin by noting that the holiday season is upon us and it’s time to suggest some books of mine that might make dandy gifts for family or friends. Here’s the deal, and it’s good through the rest of this month and all of December. Take 10% off on any one of my books you purchase (see list below—shipping is $6), 20% off if you buy two books (shipping is $9), and 25% off, plus free shipping, if you buy three or more. For this special, mail orders only please (no PayPal)—check or money order is fine. Here are the books included in this offer and their regular retail prices:

Lords of the Veldt & Vlei: Africa’s Pioneer Hunters.

Regular edition $45.

Deluxe numbered edition $75.

Here are some comments from authorities in the field:

“This book takes us back to the years 1837-1910 when the first English and European hunters were going into Africa. With Jim Casada as a guide, we follow now-legendary hunters into Africa’s greatest gamefields, where their adventures tested their survival as much as hunting skills. As an authority on African hunting and the authors who have published books on the subject, Jim has no peers.” Lamar Underwood, former editor of Sports Afield and Outdoor Life and noted compiler of anthologies on subjects ranging from hunting and fishing to survival.

“Jim Casada exercises his able research and writing skills to bring to life many of the early hunting icons who dared to enter the dark world of mostly unexplored Africa in search of exploration fame, adventure, and fortune. This book brings the glory days of African hunting to the reader in an entertaining style and can be a springboard into deeper understanding of some of the most interesting and daring hunters in history.” J. Wayne Fears, author of Hunting North America’s Big Bear, The Complete Book of Outdoor Survival, Hunting Whitetails Successfully, and numerous other books.

Fishing for Chickens: A Smokies Food Memoir, was released late last year by the University of Georgia Press. I’m quite pleased with how it turned out and the job the publisher did with it. The 330-page book features dozens of vintage black-and-white photographs, a glossary of Smokies’ food terms, an annotated bibliography of books on the region’s foodways, well over a hundred old- timey recipes, and both a general index and a recipe index. The heart of the book though, and certainly the part of it in which I take the greatest pride, is precisely what its sub-title suggests. It is narrative coverage, in twenty-four chapters, of how folks raised crops and livestock; gathered foodstuffs from nature’s rich larder; canned, cured, and preserved their edibles; and the folkways of food in general. $28.95.

A Smoky Mountain Boyhood: Memories, Musings, and More. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 2019. Paperbound. Illustrated. xvi, 309 pages. A warm and wistful look back on the Smokies as I knew them when a boy–the grand characters, daily way of life, family, work and play, food, and the essence of a wonderful time and place. The book has won multiple awards so evidently I managed to convey the magic of my youth in meaningful fashion. $29.95.

Jim and Ann Casada, The Complete Venison Cookbook. Rock Hill, SC: High Country Press, 2012. Softbound 202 pages. Originally published by Krause Publications, this book did very well before they inexplicably took it out of print. After some thought I had it reprinted and it continues to be a favorite with deer hunters and venison lovers. The work contains more than 250 scrumptious original recipes on the preparation of venison and our best-selling book ever. We tested every recipe and ate venison twice a day for six months while doing the book. A real bargain at $15.

Jim and Ann Casada, Venison Cookbook: From Field to Table—400 Field- and Kitchen-Tested Recipes. Stackpole Press, 2023. Softbound. 264 pages. This one came out just a couple of months back and it brings together recipes from earlier cookbooks with updated and expanded narrative material on dressing, processing, aging, and other aspects of readying meat to eat. Softbound. 264 pages. $24.95.

Jim Casada, The Literature of Turkey Hunting: An Annotated Bibliography and Random Scribblings of a Sporting Bibliophile. Hardbound in a slipcase. The book is a limited, signed, and numbered edition of 750 copies with all edges gilt, a ribbon marker, Skivertex cover, Skivertex slipcase, and all the attributes of a limited edition “done right.” A must for the serious turkey collector. $100 postpaid and insured.

Jim Casada, Remembering the Greats: Profiles of Turkey Hunting’s Old Masters. Hardbound in dust jacket. Illustrated with over 100 vintage photos, this book, which won multiple awards, profiles 27 of the sport’s icons. $35.

Jim Casada (Editor), America’s Greatest Game Bird: Archibald Rutledge’s Great Turkey Hunting Tales. Columbia, SC: USC Press, Hardback in dust jacket. I would also note that I have an extensive collection of original Rutledge books as well. Visit the Rutledge list on my website for details. $30

Jim Casada (ed.), Bird Dog Days, Wingshooting Ways. Columbia, SC: Bird Dog Days, Wingshooting Way: Archibald Rutledge’s Tales of Upland Hunting. Columbia, SC: USC Press, 2016. Hardback in dust jacket. xx, 180 pages. Includes my lengthy Introduction and a bibliographical essay. A collection of 23 of Rutledge’s finest stories on bird hunting and bird dogs. $30.

Jim Casada (ed.), Hunting and Home in the Southern Heartland: The Best of Archibald Rutledge. Columbia, SC: USC Press, 1992. Hardback in dust jacket. xii, 263 pages. Thirty-five of Rutledge’s most beloved and enduring stories told as only he could relate a tale. Includes my detailed input on Rutledge the man, commentary on the stories, a full bibliography, and other information. Armchair adventure at its best. $30.

Jim Casada (ed.), Tales of Whitetails: Archibald Rutledge’s Great Deer Hunting Stories. Columbia, SC: USC Press, 1994. Hardback in dust jacket. xii, 281 pages. Thirty-five of Rutledge’s great deer hunting stories with my editorial input similar to that noted above. A must for those who cherish great storytelling or deer hunting. $30.

**********************************************************************************

As last month’s newsletter indicated, I have a lifelong affection for October that amounts to a mental love affair. Yet in some ways my affinity for November is almost as strong, with nostalgia being the spice that makes the month so significant to me. It’s difficult to capture the nature and depth of that longing look back to all that the month has meant to me over the years, but in the snippets that follow I’ll try to offer something of an index to why the month means so much to me.

FAMILY MEMORIES

My daughter Natasha and granddaughter Ashlyn

November somehow stands out in my mind in a special way when it comes to family memories. Many of those fond recollections are closely intermingled with the food and hunting memories that follow, and in some ways I guess it’s strange that the month looms so large in my mind. After all, in terms of extended family, it didn’t see any more exposure to them than summertime visits from out-of-town uncles, aunts, and cousins. As for kinfolks who lived locally, we saw and visited with all of them—not only Grandma Minnie and Grandpa Joe but aunts, uncles, and cousins, on pretty much a weekly basis (or more often at some seasons).

Still, November somehow stands out. I think several “little” things explain this. By this time of year leaves were gone, the landscape bare, some types of outdoor activities (though certainly not hunting) limited, and the grey, often gloomy nature of the world about one made closeness to hearth, home, and loved ones more important. A fine example came when I was a freshman in college. In a striking change from today’s world, classes and the normal routine of campus life scarcely altered at all during Thanksgiving week. There was a special chapel service and better food than usual in the dining hall on Thanksgiving Day, but no boarding students went home, classes resumed after a one-day break, and that was that. For me, it translated to intense loneliness, at least during my freshman year, and looking back I reckon I was about as low as at any time in my life prior to my wife’s death a few years back. In truth I felt sorry for myself, not only because of missing the abundant joy of family feasting but also because I was missing the opening of rabbit hunting season for the first time since I was old enough to tag along on hunts.

Another reason the month stands out is that I came from a family where thankfulness was an active, meaningful, and heartfelt part of the month drawing to a close. We had food aplenty; enough money to get by, pay bills, see everyone decently clothed (but not much more); and we had each other. There wasn’t a lot said about togetherness, but the sense of it was always there, strong and sure. I sensed it with my grandparents, who had known little but hard times, hard work, and near poverty all their lives; even more so, it was palpable with my parents, and especially my mother. Her mother had died when she was an infant, she was raised by relatives in a situation where love was in short supply and where she seldom lived in the same place for more than a year, and obviously she was determined that HER family would be dramatically different on that front. When she and Daddy bought the house in which I was raised, she said, according to Daddy, “I don’t ever want to move again.” For the better part of six decades, until the final weeks of her life, she didn’t. Often, at this time of year, I think about that sense of place and the pleasure of being in a fixed location.

FOOD MEMORIES

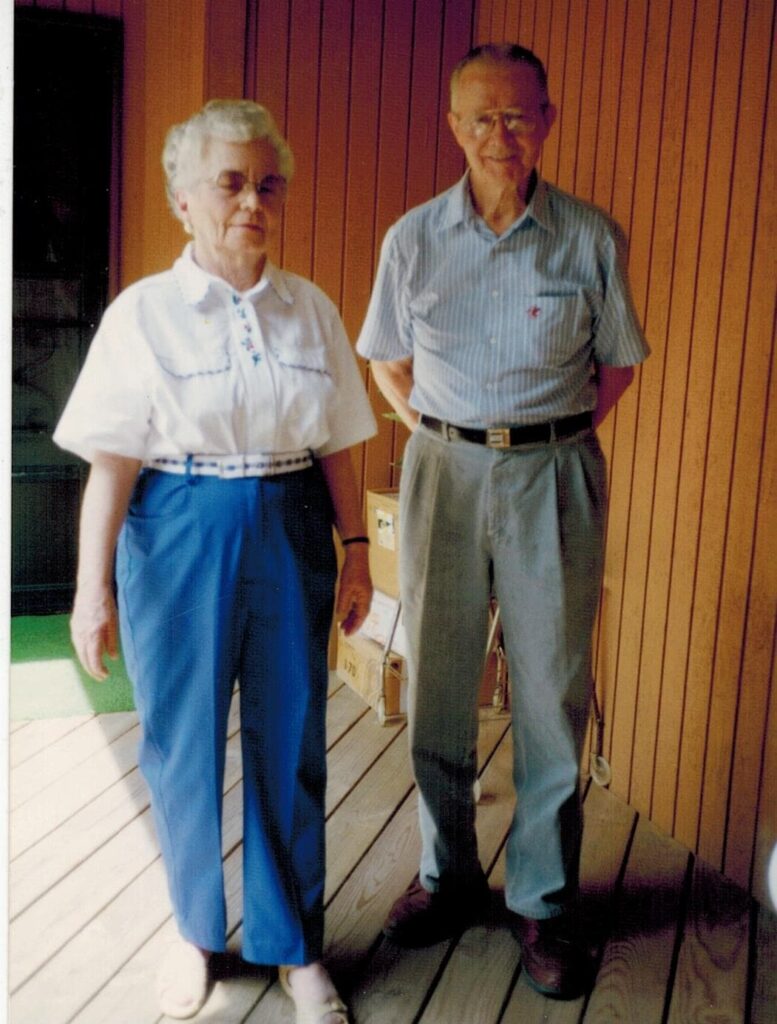

My parents Anna Lou and Commodore 1993

As these words are being written the alluring aroma of a big pot of apples cooking on the stove is wafting through the house. The smell is part spice, part sweet, part juiciness, part a big pat of butter in the mix, and all pure wonder. When it comes to simple yet scrumptious eating, what the mountain folks in the land of my raising sometimes called “chunky applesauce” stands out right at the top of the list of tastiness. Maybe it’s because we had a little orchard when I was a boy and ate apples at least twice a day at this season of the year, or perhaps it’s just memories of Mom’s loving and hardworking hands endlessly peeling, coring, cooking, and canning apples. Or maybe it’s the myriad ways she prepared them—her signature applesauce cake, apple cobbler, fried pies from dried apples, apple butter, fresh apple cake, and much more. Nor will wonderful memories of Grandma Minnie’s signature stack cake, with reconstituted dried apples redolent with all the fruit’s flavor forming a layer between each of the seven thin cakes she carefully placed atop one another, ever leave me.

But it wasn’t just apples. There were treats from pumpkins, persimmons, and pawpaws. Nourishing nut tidbits, eaten by themselves or infused into all sorts of sweet treats, from black walnuts, hazelnuts, hickory nuts, and our two towering Chinese chestnut trees added to the fall bounty. Nor should cornfield beans, leatherbritches, cushaws, acorn squash, turnips and turnip greens, and other foods of the season be forgotten. It was the season for celebrating nature’s ample bounty, and as an extended family we did so every Thanksgiving.

November was also the month of hog killing, a demanding undertaking that required many willing and knowing hands, but for me as a boy it was pure joy and excitement to such a degree I never considered it work. Hog killing was a family affair, with Mom and Dad, various aunts and uncles, and of course Grandma Minnie (supervisor and matron-in-chief for all aspects of the undertaking after Grandpa Joe (the man in charge when it came to killing the hogs, directing the gutting and skinning, and getting things ready for Grandma and her helpers) as the leaders of the clan. I loved everything about it from the carefully placed .22 shot to the hog’s brain right through the last of the fat being rendered, cracklings skimmed and canned, sausage fried and covered in lard in quart jars, and of course eating beyond compare of fresh pork. There may be something in the meat line finer than properly prepared backbones-and-ribs from a freshly killed hog, but if so it has to be fried tenderloin from the same pig. My, what meals those were to reward the hardworking crew on hog-killing day and for several days to come. Then, over the ensuing months, there would be cured ham, red-eye gravy, sausage gravy from the canned meat, and steaming crackling cornbread. Anyone who has never been a part of hog killing and the feasts that followed, and in today’s world that’s probably 99 percent of the population, has missed a grand experience.

HUNTING MEMORIES

My fond hunting memories associated with this month are quite varied. They include the delights of a number of fall turkey outings with dogs, an aspect of the sport many have never experienced, with a good friend up in Virginia. That fellow, Tom Saunders, had a turkey dog named Jenny that was a canine wonder, and to make things even better, many of those hunts also saw the day end with an hour or two of muzzleloader hunting for deer. Then there have been other deer hunts, mainly where I live, during this month that sees the peak of the rut here in South Carolina.

Yet the two most powerful and enduring recollections of being afield in November belong to the earlier part of my life; specifically my teenage years and a Thanksgiving spent with in-laws early in my marriage to Ann. Dad was a beagle loving, rabbit hunting fool, and I was fortunate enough to grow up in a time and place when cottontails were plentiful. On a big all-day outing, usually involving two or three adults and a comparable number or more of teenage friends of mine, we might well bag twenty rabbits. Anything under ten was a rather poor outing. The rabbit season always opened Thanksgiving week, and that mean the latter part of November was filled with being afield not long after daylight, often with a frost so heavy that, as a friend once described it, “you could track a rabbit in it.” We never did that but on such mornings it wouldn’t be long before the joyful chorus of beagles hot on a trail rang through the chilly stillness. Soon a gunshot would follow and a day filled with pure wonder was off to a fine start.

How I loved those hunts and even now, looking back many decades into the past, I can hear Daddy shouting, “There he goes” and then calling the dogs (we never shot at the first couple of rabbits we jumped, wanting the dogs to get the kinks worked out and in proper fettle for the day).Then came the distinctive voices of generations of canine companions with names such as Lead, Lady, Chip, Dale, Tiny, Bugle, Queenie, and a host of others. When I went off to college and was terribly homesick my first year, there was absolutely nothing I missed more than those November rabbit hunts.

My other enduring memory involved a Thanksgiving week quail hunt with my father-in-law. To put the best possible spin on matters, my wife’s parents did not think highly of me when we married. They believed, rightly, that their only child had married beneath her, and my mother-in-law in particular had singularly little use for this upstart hillbilly who had somehow wangled his way into the heart of a Southside Virginia belle. Her disdain influenced her quiet husband, but for him at least matters changed somewhat when we spent a Thanksgiving with them either my first or second year in graduate school.

Her father had arranged to borrow a pointer belonging to a friend and that same fine fellow had given us permission to hunt his expansive, quail-filled farm. There were birds everywhere and the pointer proved to be an old-time working dog of the first rank. We seemed to be easing up on a covey point or follow up singles every quarter of an hour or so, and our game bags began to fill in gratifying fashion. Or, to be somewhat more specific, the pouch of his Duxbak jacket became increasingly weighty and I had just enough birds to realize I was, so to speak, in the game.

Mind you, I was seriously handicapped, no matter that he graciously gave me the first shot every time a bobwhite took wing. The only scattergun I owned at the time was a 20 gauge Stevens choked tight as Dick’s hatband while he carried a Browning semi-automatic with a cylinder choke. He could fire it so fast, with a bird falling far more often than not, that it seemed to me almost an automatic. That fine day’s outing, followed by a feast of fried quail, cathead biscuits, gravy, and all the trimmings, bridged a gap between us. He realized that possibly, just possibly, there was more to his n’er-do-well son-in-law than a dirt poor son of the Smokies trying to get through graduate school. From that point forward he viewed me differently and far more favorably, and the following spring when I showed him how to wreak havoc on bedding bream with a fly rod and popper my status rose a bit more.

It’s good to look back on such things, and for me they carry a lesson applicable to all of life. Namely, it is good to hold your friends close and cherish their company. It is even better to love your family and realize that times spent with them are building up a treasure house of far greater value than anything you can acquire with money.

JIM’S DOIN’S

It turns out that the last month or so saw a bit more activity from me in terms of things appearing in print. As always there’s my weekly column in the hometown paper in Bryson City, NC, the place of my raising, the Smoky Mountain Times. Of late I’ve been writing a series of pieces on “Those Were the Days” that look at practices which were once common and now have vanished or threaten to do so—hitchhiking, riding bikes to go somewhere, kids spending most of their free hours outside playing, corporal punishment in school, and much more. Beyond that, here’s a listing of recent publications: “Bear Scare” (Mollygrubs Messer—Part 7), “Sporting Classics Daily,” Oct. 19, 2023;“Traditional Mountain Character Traits,” “Blind Pig & the Acorn, Oct. 24, 2023;“Urination Tribulation,” “Sporting Classics Daily,” Oct. 26, 2023;“Conservation Chronicles,” Sporting Classics, Nov./Dec., 2023, pp. 123-27;“Trails to Tombstones,” “Blind Pig & the Acorn,” Oct. 31, 2123;“Mountain Soul Food,” “Smoky Mountain Living” (on-line), Nov. 3, 2023;“The Delight of Fruit Salads,” Smoky Mountain Living, Dec./Jan. 2023-24, pp. 20-23;“Thankful November—Baked Acorn Squash,” “Blind Pig & the Acorn,” Nov. 13, 2023; “Mollygrubs Messer—“Of Pointers and Polecats,” “Sporting Classics Daily,” Nov. 14, 2023; “Slickrock Creek: The Delights (and Difficulties) of Remoteness,” “On the Fly South,” November.

******************************************************************************

THIS MONTH’S RECIPES

All of the recipes that follow come from my award-winning food memoir, Fishing for Chickens, and all belong to the holiday season embracing Thanksgiving and Christmas. I’ve included some of the narrative material so you can get a sense of what the book is like and hopefully be sufficiently intrigued to order a copy.

CHESTNUT DRESSING

Both my father and grandfather frequently spoke of the “good old days” when the American chestnut was the dominant tree in the Appalachians as well as a dominant force in their livelihood. Grandpa Joe cut chestnut timber for “acid wood,” fence rails, shingles, and rough lumber for building barns and outhouses. Each autumn when the nuts were ripe and falling, the entire family would set out on all-day nutting expeditions. They collected bushels of them. Some were for family use—eaten raw, roasted at the open fire place which served as the source of heat in their home high up in the hollow of Juney Whank Branch, boiled, and consumed in other ways. Much of the harvest, however, was sold for what Grandpa always called “cash money,” with the redundancy being merited because it was so scarce. The chestnuts not consumed or saved for future use by the family were destined for the stands of street vendors in big cities who sold piping hot chestnuts at intersections and other busy locations.

The meaty, nutritious nuts were also an important for fattening hogs, and traditional killing and butchering time came shortly after what might have been called chestnut season. That found free-ranging pigs in prime condition from consumption of chestnuts, and often as a youngster I heard old-timers say: “You’ve never tasted fine pork until you’ve eaten a chestnut-fattened hog.”

They were even so important that my father often reminisced of how he and other family members would, especially in December and January, observe chipmunks closely to note where they had holes in the ground. Often a bit of digging in such holes with a mattock would unearth a cache of a quart or two of chestnuts. They were particularly prized because chipmunks and squirrels somehow always recognized when a nut was bad and never stored it.

By the time I was born, the dominant tree of the eastern forests was already long gone. Most of the trees in the Smokies of my boyhood died in the late 1920s and early 1930s, but the family kept up a long-established tradition by substituting Chinese chestnuts for the real thing in dressing. Here’s the recipe used by Grandma Minnie and Mom and subsequently, by my wife. Incidentally, if you don’t have access to chestnuts just substitute pecans.

6-8 cups cornbread crumbs (homemade cornbread is infinitely preferable to using purchased crumbs, and that is doubly so if you make it with stone-ground meal). Using buttermilk to make the cornbread makes it much lighter (see the recipe above).

½ cup butter

Place the butter in a skillet and add:

1 cup cooked, chopped chestnuts

1 cup finely diced celery

1 cup finely chopped onion

Cook slowly over low heat for ten minutes. Stir frequently as the mixture burns easily. Add this to cornbread crumbs and mix well. Add two eggs well beaten and two cups turkey or chicken broth (or stock). Add more liquid if necessary as the mixture must be very moist, indeed almost runny. Season to taste with salt, black pepper, sage (if you like it—I don’t and it is a dominant and dominating taste), Montreal Chicken Seasoning, or whatever you prefer). Bake at 350 degrees for forty to forty-five minutes.

GIBLET GRAVY

While I thoroughly enjoy dressing with a slice of turkey or by itself, it really cries out for a lavish ladle of giblet gravy poured over it. I’ll leave the gravy-making details to your individual tastes, but I do have a suggestion (at least for turkey hunters) that will make it meatier. The next time you kill a wild turkey, save not only the giblets (heart, liver, and gizzard) but all of the dark meat (legs, thighs, wings, and medallions on the back). Place the dark meat in a large stock pot and keep it simmering for at least a couple of hours. The meat will never get really tender, but it will reach a point where you can remove it from the bones. Do so, and keep the stock as well. Chopped into small pieces and frozen with the giblets (add them in the final half hour of simmering), you have the makings of giblet gravy richly laced with tasty, nutritious bits of wild turkey. Combine it with some of the stock you saved and the juices from your baked domestic turkey, and you can produce an abundance of gravy and have the good feeling associated with fully utilizing your wild bird.

SMOKY MOUNTAIN STACK CAKE

This delicacy, so closely associated with festive occasions in the Smokies, has been mentioned repeatedly throughout these pages. That’s easily explained, because as a dessert it looms that large in the region’s culinary traditions. Here’s the way Grandma Minnie prepared her stack cakes, although she “measured” by eye and a lifetime of experience rather than with specifics.

4 cups flour

1 teaspoon salt

½ teaspoon baking soda

2 teaspoons baking powder

½ cup shortening

1 cup sugar

1 cup sorghum syrup

1 cup sweet milk

3 eggs

Sift dry ingredients except sugar together, cream the shortening, then add and mix in sugar a little at a time. Add sorghum molasses and blend thoroughly. Then add milk and eggs, beating until smooth. Pour batter a half inch deep in greased nine-inch pans. The batter should be sufficient for seven layers, which for Grandma was the magical number.

After the baked cake layers have been removed from the oven and cooled, add sauce made from dried apples between each layer and place stack cake in a closed container or the refrigerator. You can also use other fillers, such as peach butter made from dried peaches or blackberry jam, between the layers. NOTE: Although many mountain cooks carefully slit each layer or individual section of cake and inserted the fruit filling between the two sections as well as between whole layers, Grandpa did not follow this practice.

PUMPKIN CHIFFON PIE

This pie has long been a favorite in my family. Both my mother and Aunt Emma made it, although with slightly different approaches. No Thanksgiving or Christmas at our home, or indeed any special occasion when pumpkins were available, was complete without “punkin pie.” When she prepared this cherished treat, Mom always made at least three or four. It was just as well, because they disappeared in no time. She used pumpkins we had grown in our garden, and the time involved in preparing them (cutting up, removing seeds, peeling, and then stewing) was taken for granted.

Prepare and bake a nine-inch pie shell our use a store-bought one

Soak 1 tablespoon gelatin in ¼ cup cold water and set aside

Beat 3 egg yolks slightly (separate and save egg whites)

Add:

½ cup sugar

1¼ cups pumpkin

½ cup milk

¼ teaspoon salt

½ teaspoon cinnamon

½ teaspoon nutmeg (freshly grated is best)

Cook and stir these ingredients constantly over hot water until they are thick. Stir in the soaked gelatin until it is dissolved. Cool.

Whip three egg whites and quarter teaspoon salt until stiff. When the pumpkin mixture begins to set up, stir in the sugar and fold in the whipped egg whites. Fill the baked pie shell and chill the pie for several hours. Serve with whipped cream (the real McCoy if at all possible).

TRADITIONAL PUMPKIN PIE

This traditional Thanksgiving dish was likewise a fixture with our family, and the fact that Momma would make both chiffon pies and this type, which is more of a standard approach, probably says quite a bit about our abundance of cooking pumpkins and enjoyment of them in pies. We always had four or five choices of dessert at Thanksgiving, but this was one of my favorites. We grew our own cushaws as well as pumpkins, and the “meat” from those or that of candy roasters will work perfectly well in this recipe.

1 cup stewed pumpkin

1 cup brown sugar

1 teaspoon ground ginger

1 teaspoon ground cinnamon

¼ teaspoon salt

2 eggs

2 cups milk

2 tablespoons melted butter

Pastry

Add the sugar and seasonings to the pumpkin and mix well. Then add the slightly beaten eggs and the milk and lastly stir in the melted butter. Turn into a pie plate lined with pastry and bake in a 425-degree oven for five minutes. Then lower the heat to 350 degrees and bake until the filling is set. The pie should be allowed to cool prior to serving.