BIG NEWS ON THE BOOK FRONT

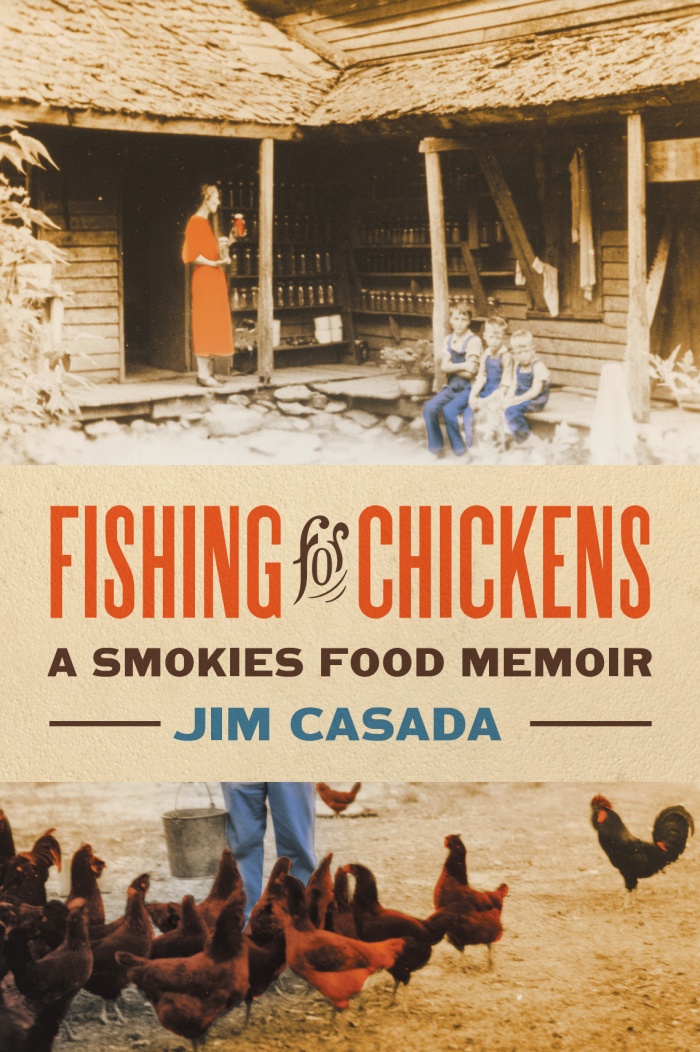

I’m delighted to report that things are moving apace with the book that might be described as a sort of companion volume or sequel to A Smoky Mountain Boyhood: Memories, Musings, and More. Recently I heard from the publicity team at the University of Georgia Press, which is publishing the book, that they have initiated the first steps of pre-publication promotion for Fishing for Chickens: A Smokies Food Memoir. An image of the book’s cover appears below. It comes from colorization (I think that’s the proper term) of vintage photographs from the Smokies. The book, which will run to a bit over 300 pages in length, is to be priced at $28.95. I’ll begin taking advance orders, with waiver of shipping, once I have more specifics on the exact date of publication.

Meanwhile, I’ll simply indicate that I’m quite excited about the work. It’s an effort to pay tribute to my culinary roots and especially to the two women at the heart of them, my paternal grandmother, Minnie Casada, and Momma, along with my beloved wife Ann, who did such a stellar job in strengthening those roots and perpetuating family food traditions. Here are some thoughts about the book from noted writers, authorities on foodways, and experts on the Smokies who have read the manuscript.

Don’t think for one second that Fishing for Chickens: A Smokies Food Memoir is just another printed collection of questionable recipes, far from it. In this fun to read book, Jim Casada uses his award-winning descriptive writing skills to invite the reader to sit at the Casada table in the heart of the Great Smoky Mountains of the 1940’s and 50’s. Here you will meet wonderful characters such as Grandma Minnie, Grandpa Joe, Momma Casada, Aunt Mag, Beulah and Jim’s beloved wife Ann. As you turn the pages of this book you will get to know these mountain folk and learn how they raised, gathered, and preserved down-home food, and turned it into mouthwatering table fare. From yard chickens to mountain trout, from apples to ramps, Jim shares four generations of food preparation lore. Each chapter is sprinkled with scrumptious recipes that will cause the reader to turn down the corner of the page and search for grandma’s cast iron skillet and some lard. This book records Great Smoky Mountains culinary traditions at their best, and Casada has made it not only an informative but an entertaining read as well.

J. Wayne Fears, author of The Lodge Book of Dutch Oven Cooking, The Wilderness Cooking Handbook, Cooking the Wild Harvest, Backcountry Cooking.

***************************************************************************

Jim Casada’s Fishing for Chickens is a superbly entertaining story-telling account of a boy’s mid-twentieth century childhood in the Great Smoky Mountains as seen from the perspective of the daily culinary activities and food production practices of the Smoky mountaineers. Casada’s deft interspersing of mountaineer foodways and folkways with lighthearted self-deprecating anecdotes captures the ethos of the domestic life of this distinctive sub-region of the Southern Appalachians like no other book of its kind. Solidly authentic, Mountain Fixin’s affords a rare glimpse into a bygone era of Smoky Mountain life.

Ken Wise, professor at the University of Tennessee Libraries and author of Hiking Trails in the Great Smoky Mountains and Terra Incognita: An Annotated Bibliography of the Great Smoky Mountains, 1544-1934.

************************************************************************************

To read Jim Casada is to sit on the porch or in front of the fireplace immersed in great conversation with a truly knowledgeable friend. Some of his books let you roam the woods, fields, and waters of his native Smoky Mountains. Others put you squarely in mountain kitchens as sure, comfortable hands prepare staples that eat like delicacies. Fishing for Chickens: A Smokies Food Memoir is rooted in the latter approach, but as is always the case with Casada, there is much more. The prose is rich and inviting, and there seems to be no aspect of mountain life, natural or man-made, he doesn’t touch on. The book promises an overview of mountain food and drink but wanders effortlessly into all the cultural and historical riches of a region and a time whose ways are unknown to too many of us. Casada brings us the realities of a life that has little of monetary value but boasts uncounted riches in the form of natural bounty combined with the ability to turn food preparation and dining into a truly enviable culture.

With Casada, both history and culture are personal. Few writers are able to share the magic and rootedness of a culture this well, for his life embodies the very DNA of the Smokies. He is a consummate tale-teller, a master of phrasing and of choosing just the right detail to bring any scene to life. His writing is, to borrow a phrase from the book, “keen as a properly sharpened Case knife.” You will find few better able to bright the sights and smells of country fare to the page; you’ll wish you could join him at the table.

Mountain ways, like so much of the American story, are slipping away. We should all be indebted to those who catalogue them for the future, and Jim Casada is in the front ranks of those undertaking the task. This book is a time machine, an encyclopedia, a travelogue, and a recipe book to boot. If you like fine writing, great eating, and the company of interesting folk, Fishing for Chickens is for you.

Rob Simbeck, author, The Southern Wildlife Watcher and former president and board chairman of the Southeastern Outdoor Press Association.

*******************************************************************************

I have dedicated 13 years of my life to celebrating and preserving Appalachian culture and heritage in the online sphere. Traditional foodways of the region are what binds the culture together. Jim Casada is a fountain of knowledge when it comes to mountain food and anyone who reads Fishing for Chickens: A Smokies Food Memoir will most certainly agree. The book weaves two of the most important features of Appalachian culture together: family and food. Jim’s latest work will stand the test of time and become not only a source of great entertainment but a historical reference for students of Appalachian Studies.

Tipper Pressley, blogger at Blind Pig and the Acorn, content creator for Celebrating Appalachia YouTube channel, and culinary instructor at the John C. Campbell Folk School.

***********************************************************************************

Fishing for Chickens is a comprehensive, and loving, guide to the grown and gathered foods that form the staples of cooking in the Great Smoky Mountains region, their preparation, and the cultural practices and customs behind each. In this work, Jim Casada aptly displays his talents as perhaps the foremost modern chronicler of Smoky Mountain life. Dig in and enjoy this literary feast that is so good it’ll “make you slap your granny.”

Dan Pierce, NEH Distinguished Professor of Humanities, UNC-Asheville; author of The Great Smokies from Habitat to National Park, Hazel Creek: The Life and Death of an Iconic Mountain Community, Real NASCAR, and Corn from a Jar.

***********************************************************************************

I was immediately drawn to the mystique of the Great Smokies through Jim Casada’s endearing and descriptive food memories. It took real discipline for me to put the book down. Jim is the real deal, reaching back three generations to give us recipes truly traditional to “place.” I’m obsessed with Fishing for Chickens: A Smokies Food Memoir and look forward to creating new memories right here in Alabama with fixin’s from this book.

Fishing for Chickens is one of the best food memoirs I’ve read. Immediately I was transported to the Great Smokies as Jim Casada descriptively introduced family traditions and place in this masterpiece. I especially love that he devotes one chapter to holidays and special events. What better way to educate through food memories and the very finest traditions of the Great Smokies. I look forward to making some of my own traditions right here in Alabama drawing on his food memories and recipes.

Stacy Lyn Harris, producer of lifestyle and cooking DVDs, TV cooking show regular including co-hosting “The Sporting Chef,” author of a number of sustainable living cookbooks including Stacy Lyn’s Harvest Cookbook and Sustainable Living, and a frequent contributor of cooking articles and columns to magazines.

NOVEMBER NOSTALGIA

A few weeks back my sister-in-law shared an article she had come across which delved into the manner in which nostalgia could impact our mood, outlook on life, mental health, and much more. Although it was far too full of academic jargon for my taste, the piece’s basic conclusion was that indulging in nostalgia was a good thing. For me, I reckon that’s a sort of relief, because it seems the older I get the more inclined I am to live in the past. That’s almost certainly a widespread human trait for those with several decades of life behind them. One of my favorite writers, Havilah Babcock, pretty well went to the heart of the matter with these words: “Boyhood improves with age, and the more remote it is the nicer boyhood seems to become.”

For me the month of November absolutely exudes nostalgia. It always evokes a variety of pleasant thoughts—fond memories of boyhood rabbit hunts with a bevy of human and canine companions, culinary joys associated with Thanksgiving, the wonderful weather the Smokies so often provide in this month, spawning brown trout on the move, and the sort of crispness in the air at daylight which fills youngsters with juice and puts a bit of added spring in an old man’s step.

The month usually brings the first heavy frosts of the year, ones that, in the words of a certified hillbilly of the first water who hails from Topton, NC and has always delighted me with his memories and vivid descriptions, Ken Roper, “are so big you could track a rabbit in them.” I would submit to you that his description captures the essence of a clear, cold November morning with intense blue skies and not so much as a hint of a breeze astir. I think back on such November days, lots of them, when frost melting as the sun’s rays hit it turned an overgrown, abandoned pasture or piece of farm land run to broom sedge into a place of wonderment. There before my eyes were a million diamonds sparkling in a fashion no ring on a fair maiden’s hand could ever hope to match. The visual wealth might have been transitory, but it was a wonderment to behold and you had the comfort of knowing that with the next heavy frost there would be a repeat performance of Mother Nature opening up her treasure chest to give humans a peek.

November also witnesses leaf fall and a distinct change in the landscape. Those who confine all their walking and wandering to warmer months miss something, because woodlands shorn of their leaves provide a different and delightful perspective. You don’t have to worry about blundering into a rattlesnake or copperhead or making a painful intrusion into a yellow jacket nest. What is far more significant though is the fact that you notice things which are all but invisible in spring and summer. Signs of one-time human presence, distant vistas which had been blocked by vegetation, sprightly plants such as galax or partridge berries which pass largely unnoticed, maybe the last, lingering red seed pods of hearts-a-bursting-with love or jack-in-the-pulpit, and their like are a feast for knowing eyes.

The month is also the time for nutting. Once that meant gathering chestnuts, but today the logical focus is on black walnuts. These wonderfully tasty treats take plenty of gumption in what Grandpa Joe would have called “the getting.” You’ve got to gather them, let the husks rot away, maybe helped along a bit by human effort, allow the nuts to dry and cure a bit, crack them, and then hull out the meats. Rest assured that the rewards are worth every ounce of effort, and there’s a lot of that involved.

Black walnuts

Mention of the noble walnut leads to passing thoughts on the walnut’s rich place in American history. It has always been a cherished wood, one which lends itself to things such as lovely gunstocks or beautiful pieces of furniture. The hulls once provided a key raw ingredient for dyeing cloth and leather, and the inedible portions of the nut, hard as the head of an opinionated son of the mountains such as yours truly, have commercial uses for polishing.

I never look at a walnut tree without thinking about my Grandpa Joe, because he could not pass a walnut tree without commenting: “Son, that’s a grandchild’s tree.” When asked for an explanation he would note that black walnuts were slow growing and required three generations to reach the point where they were ready to be cut for saw logs. He was right, because on the old home place where he and Grandma Minnie once lived, some of the black walnuts which lined the path leading to the chicken house and the pig pen now have reached a point where, if harvested, they would provide two (and in a couple of cases three) saw logs from which 12-inch boards could be cut. The family presence there is long gone, but a few years back the current owners graciously allowed my brother, me, and a cousin who was visiting from Chicago but had fond childhood memories of the place, to walk the grounds. Many things caught my eye, but the stately walnut trees were right up in the front rank in terms of nudging distant memories back to the surface.

One other thought comes to mind while I’m musing on black walnuts. They are an excellent signpost for one-time human presence. While existence of a mature walnut tree in a remote area of woodland, national forest, or national park doesn’t guarantee that folks once called the site home, it’s mighty suggestive in that regard. Walnuts are a hardy tree, and their nature is such that not a whole lot of competing vegetation springs up where they are found, so the knowing eye can pick them out in the November woods without much trouble.

I always kept a keen eye out for walnut trees as a boy (and still do today), although I must admit that gathering nuts was not the primary reason I sought the tree. Rather, if there was a tree at the edge of a field or along a fence row, something easily spotted when a party of us took to the fields on a rabbit hunt, there was always the possibility of a squirrel or two being nearby. I’d give the limbs a thorough look-see, searching for a tell-tale budge or something which looked a bit out of place. Occasionally I would be rewarded and a bushytail would add a comforting bit of heft to the game bag of my hand-me-down Duxbak hunting coat.

Thoughts of that old hunting coat, and Duxbak attire in general, strike a distinctly nostalgic chord with me. In the 1950s and 1960s Duxbak was THE choice when it came to field clothing. Camo attire was unheard of, but the stiff, sturdy, enduring nature of Duxbak was another story entirely. To my knowledge today’s world of outdoor clothing has nothing approaching it in terms of combined cost and durability. I know that I would no more have thought of going afield without Duxbak pants, vest or jacket, and cap than I would have skipped a Saturday rabbit hunt to hang out in the local drug store or even visit my girl friend of the moment. One did, after all, have to have priorities. Duxbak has gone the way of so many other fine America-made products, but I’m guessing that the majority of folks reading these words are on the north side of fifty years of age, and those who hunted as youngsters will remember the brand with fondness. I know that on a personal level such was the case, and it was a sad Christmas when my gifts didn’t include one of four things—Duxbak attire of some kind, a new knife, a box of shotgun shells, or new long handles.

Those are some of the thoughts which course through my mind this time of year, for November is a month somehow meant for nostalgia. With the harvest done and winter ahead, it’s ideal for looking back in longing, and that’s precisely what I’ve been doing. That retrospective viewpoint also figures in the recipes at the end, with all of them featuring the culinary joy provided by black walnuts.

THIS MONTH’S BOOK SPECIALS

The Babcock quotation I used at the outset of my commentary on “November Nostalgia” comes from a book which I co-edited and compiled with a longtime friend and editor at Sporting Classics magazine, Chuck Wechsler. The work was Passages: The Greatest Quotations from Sporting Literature. The work is chock full of wisdom from sport’s greatest writers and offers hundreds of quotations, most drawn from the popular back page offerings that appear in each issue of the magazine (the concept was one which I’m proud to say came from me decades ago). If you would like a copy of the book, which would make a great gift for a sporting buddy, I’ve got about a dozen copies of the 200-page work available for $15 postpaid.

While speaking of books as holiday gifts, I’ve got two other works at bargain prices. Both are compilations of writings by Archibald Rutledge that I selected, put together, and supplied with editorial commentary. They are Tales of Whitetails: Archibald Rutledge’s Great Deer Hunting Stories and Bird Dog Days; Wingshooting Ways: Archibald Rutledge’s Tales of Upland Hunting. Each of these normally retails for $29.95, but from now until December 15 I’m offering each of them at $17 postpaid. There is a caveat with all these special offers. Payment must be by check or money order and made directly to me (Jim Casada, 1250 Yorkdale Drive, Rock Hill, SC 29730). Between fees and the headaches of revising order forms on PayPal, using it is too much of a stretch. Also be sure to check out my website, www.jimcasadaoutdoors.com, where you’ll find thousands of books on a number of different lists on offer.

JIM’S DOIN’S

Recent weeks have been full and fulfilling for me. It has been good to be “out and about,” as an uncle of mine liked to put it, and even though I’m fairly comfortable wearing the garments of a recluse the need for interaction with friends has ample appeal. The South Carolina Outdoor Press Association (SCOPe) held its annual meeting late last month, and this was the first of the writer organizations to which I belong to do so since the onset of the whole coronavirus mess. We had a delightful, well-attend gathering in Aiken, SC, hosted by the regional tourism group, Thoroughbred Country (www.TBredCountry.org) and its four-county area of coverage (Aiken, Allendale, Bamberg, and Barnwell counties). It’s a lovely part of the state with fine hunting, fishing, and opportunities for non-consumptive outdoor recreational activity. As was often stated at the conclusion of reports on local social events in weekly newspapers of yesteryear, “a good time was had by all.”

On a personal level, a significant contribution to the pleasure of the experience was being recognized for my efforts as a writer and photographer in SCOPe’s yearly excellence in craft competition. Most writer organizations have such contests, and they offer an opportunity to have your work judged against that of your peers and learn from the success of others as well as discover what critics think of your efforts. I was wonderfully blessed at this conference since five of my entries were recognized—four with first place awards and one with a second place. The second place was for A Smoky Mountain Boyhood, which I have also been notified has been recognized by the North Carolina Society of Historians, a venerable group devoted to the preservation and recognition of works on the history of the Old North State, with an Award of Excellence. These plaudits for the book come close on the heels of it receiving a first place award in the annual craft competition of the Southeastern Outdoor Press Association. In that competition, one judge said the following: “This book really impacted me with the exceptional way it made me feel like I was right there in the Smoky Mountains growing up. Loved every word!” Since the book is one which came straight from the heart and represents a great deal I hold near and dear, these honors are deeply meaningful to me and hopefully indicate that I somehow managed to capture the essence of what I now know was a magical youth.

RECENT READING

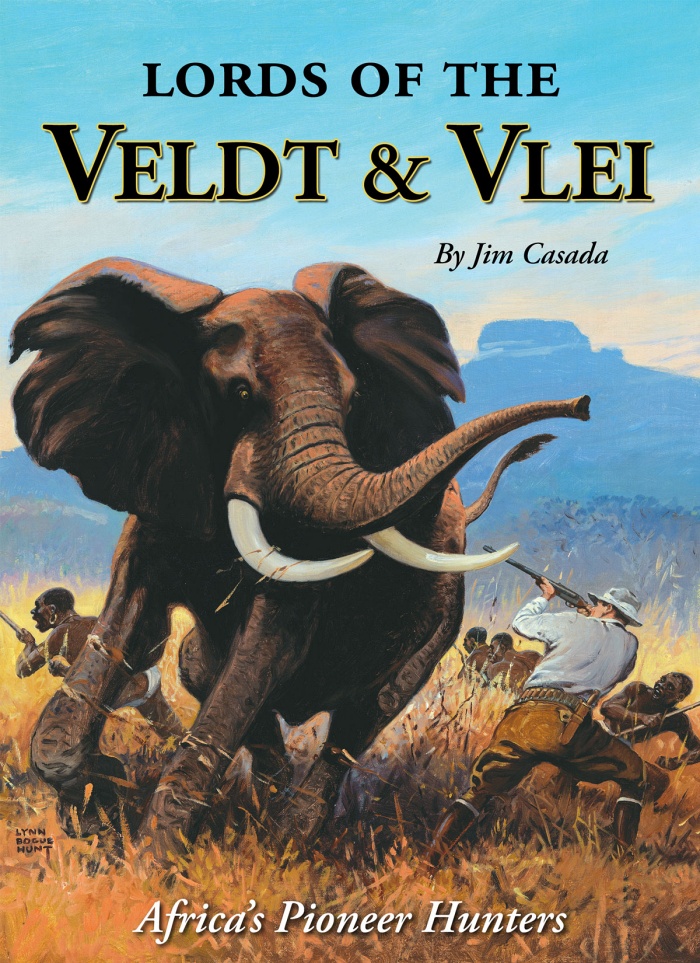

Thanks to work on a book which is now pretty much ready for publication, although finding suitable paper and printers who can get enough employees to accomplish such things is a real bugbear, a fair amount of my recent reading has involved delving into some of the grand classics of African hunting in the Victorian and Edwardian eras. The book coming out of this, Lords of the Veldt and Vlei: Africa’s Pioneer Hunters, is the first of a projected trilogy that will carry the saga of African sport from its beginnings through the golden years of the middle of the 20th century and beyond. Among the grand sportsmen/authors profiled in the forthcoming book are Sir Samuel Baker, Fred Selous, Cotton Oswell, Theodore Roosevelt, Parker Gillmore, and Roualeyn Gordon-Cumming. I’ve read and re-read books by these men and the dozen others I cover, but I always find something new and delightful with each revisit. If you are looking for the best, I’d particularly recommend Baker and Selous along with the inimitable TR.

RECIPES

Walnuts should be considered a culinary treasure. They are devilishly difficult to find in stores, and the prices you pay when they are located will, as my father once put it when he learned just how costly a cake utilizing them would be if the baker was paid a fair rate, “sour your stomach.” If you can find them at all they will cost $15 a pound or more. Fortunately, they have such a distinctive and piquant taste that relatively small amounts go a long way. None of the recipes below require more than a cup and a half.

BLACK WALNUT AND BANANA BREAD

½ cup vegetable oil

1 cup sugar

2 eggs

2 cups very ripe bananas, mashed with a fork

2 cups flour

1 teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon baking powder

½ cup finely chopped black walnuts

Mix vegetable oil, sugar, eggs and bananas well. Add flour, salt, baking soda and walnuts and mix until thoroughly blended. Place in greased loaf pan and bake at 350 degrees for an hour or in four small loaf pans for 40 minutes.

TIP: Ripe bananas can be frozen, and it is also often possible to pick them up in grocery stores at greatly reduced rates.

TIP 2: Small loaves make a nice addition to a fruit basket or hostess gift.

BLACK WALNUT CAKE WITH BLACK WALNUT FROSTING

1 cup butter (no substitute)

½ cup solid shortening

3 cups sugar

6 eggs

3 cups all-purpose flour, sifted

1 teaspoon baking powder

1 teaspoon vanilla

1 cup milk (half-and-half)

1 to 1 ½ cups chopped black walnuts

OPTIONAL: For a more moist cake, use 8 ounces of sour cream

Cream margarine and shortening thoroughly; beat well. Gradually add sugar and cream until light and fluffy. Add eggs one at a time and beat well after each addition. In a separate bowl sift flour and baking powder and add walnuts. In a measuring cup, add vanilla to half-and-half. Add flour and walnut mixture alternately with half-and- half to creamed mixture. Blend and mix well—beating well is the secret to a successful cake. Pour into a prepared 10-inch tube pan and bake in a 325-degree oven for 1 hour and 15 minutes or until done (do not preheat oven). When done, cool 10 minutes and remove from pan. Cover with Black Walnut Frosting.

BLACK WALNUT FROSTING

1 stick butter, melted

1 box confectioner’s sugar

half-and-half milk

½ cup black walnuts

Blend melted margarine and confectioner’s sugar. Add enough milk to reach correct consistency. Stir in walnuts and frost the cooled cake.

BLACK WALNUT VINAIGRETTE DRESSING

¼ cup chopped black walnuts

¼ cup chopped English walnuts

Salt to taste

¼ cup vegetable oil

2 tablespoons wine vinegar

4 teaspoons freshly squeezed lemon juice

Grated peel of one lemon

Freshly ground black pepper

Toast nuts and cool. Briefly chop nuts in blender with salt. Do not chop nuts too finely; chunks should remain. Add oils, vinegar, lemon juice, lemon peel and pepper; pulse to blend. Taste to adjust flavors. Wonderful over a mixed greens salad, sliced tomatoes, or an avocado half.

TIP: If you are especially partial to the rich, nutty flavor of black walnuts, double up on them and leave the English walnuts out.

BLACK WALNUT ICE CREAM

6 cups whole milk

1 ½ cups sugar

¼ cup flour

½ teaspoon salt

4 eggs, slightly beaten

1 tablespoon vanilla

½ pin whipping cream

1 to 1 ½ black walnuts (chopped fine)

Place milk in double boiler and heat. Mix sugar, flour and salt. Add enough hot milk to sugar mixture to make a paste. Stir the paste into hot milk. Cook until the mixture thickens slightly, and then gradually add the hot milk mixture to eggs. Cook about two minutes longer. Cool quickly in refrigerator (it is best to cool the custard mixture overnight). Whip cream slightly and add to the custard along with walnuts. Pour into ice cream churn and freeze by manufacturer’s instructions or until quite firm.