JANUARY’S MYRIAD JOYS

Ledbetter Creek is a small stream which empties into the Nantahala River

in the upper end of the Gorge.

January as I remember it from boyhood was a month for doing several of the things which run as strong and consistent threads in the fabric of my life. In the North Carolina high country of my boyhood January was usually the coldest month of the year and often the one with the most inclement weather. That didn’t bother me a bit, because I felt pretty much bullet proof and weather which now finds me staying inside in a comfortable easy chair was appealing and even a challenge. Besides, if it turned sho’ nuff nasty, I always had books as companions. The latter situation has not changed at all in adulthood. Seldom indeed does a day pass when I don’t read at least 100 pages, and I usually have two or three books going simultaneously. That’s just my habit.

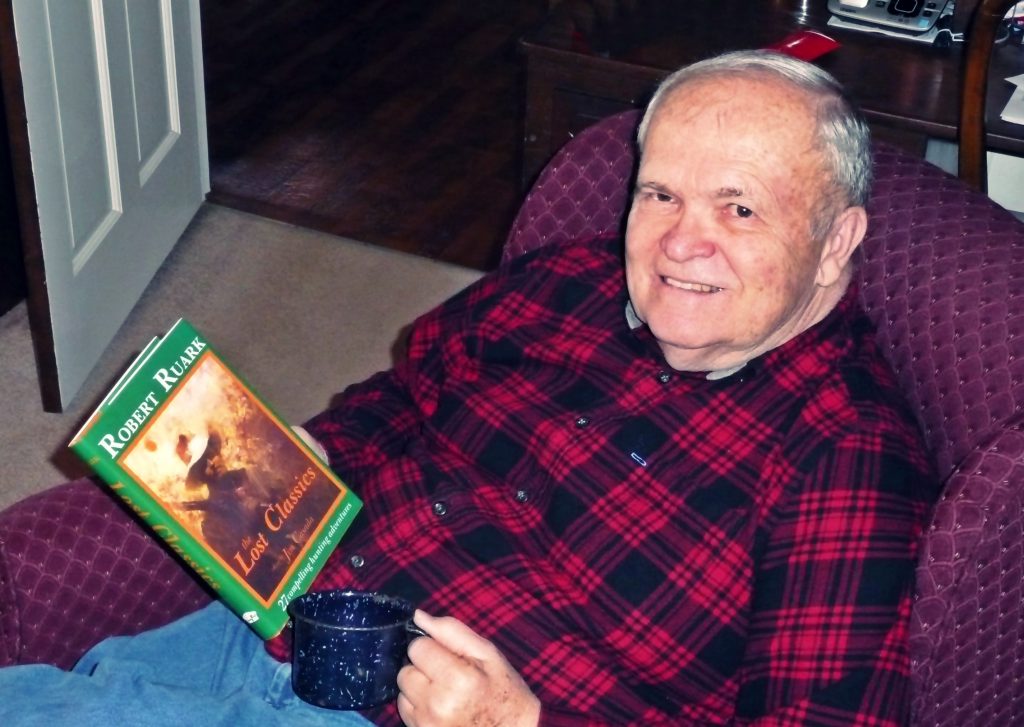

Sitting in an easy chair with a book on Robert Ruark, my favorite outdoor writer, that I edited. In my other hand is a coffee cup holding hot chocolate (I don’t drink coffee). That cup holds a special place in my memory, because it came from a lifelong buddy and was once a utensil at the fabled Bryson Place. There’s a chapter, “Tale of an Old Coffee Cup,” devoted to it in my latest book, A Smoky Mountain Boyhood.

As for reading tastes, they lean heavily in the direction of the things I cherish in life —Appalachian history; biographies of sportsmen, naturalists, explorers, and writers; folkways; and a steady dose of mysteries and adventure tales (favorites include John Buchan, P. D. James, Agatha Christie, about any of the classic British “whodunit” authors, Wilbur Smith, and Trevanian), and you get the gist of it. Of course I long since exhausted all of the stuff from the likes of Zane Grey and Louis L’Amour, and I read Ruark’s The Old Man and the Boy at least once a year. In my view it’s that good; in fact, I consider it the greatest American book on the outdoors.

I also try to read the occasional bestseller, although more often than not these days I’m disappointed. A prime recent example would be Delia Owens’ Where the Crawdads Sing. I was already familiar with her works in natural history, but her recent blockbuster disappointed me to the point of absolute vexation. First of all, there are so many impossible facets to the book as to render it ridiculous in my view. Fiction is one thing; stretching credibility until it snaps something else. Then there are the nonstop mistakes of a factual nature. I assume she spent considerable time in North Carolina, but if she did so she was blissfully unaware of the world around her. She has key figures in the work repeatedly travelling from the state’s coastal regions to Asheville to pick up items available only in cities. The only problem is that Asheville is a long day’s drive (eight hours or more) from the swamp regions of the state and there are at least half a dozen major metropolitan areas closer. Then there is abysmal ignorance about local natural history (one would have thought it would be a strong point for Owens) and an absolutely unbelievable plot line. In short, I completely fail to understand how so many folks found this a work of wonder. To me, other than some slick writing at points, it is singularly disappointing dreck.

A snowy scene from Brasstown, NC.

Along with reading, January days have always meant small game hunting in my world. I actually cherished any heavy snowfall when I was a youngster, because it meant a day or two off from school and the chance to wander around all day imagining I was a mountain man or at least a hardy pioneer. It was also a grand time to read sign, because a soft snow meant you could check out everything from well-used rabbit runs to places frequented by muskrats and ‘coons. I was never a particularly savvy or successful trapper, but I ran a small line and caught a fair number of muskrats, the rare mink, ‘coons, ‘possums, and the occasional feral cat. Similarly, I made my own rabbit gums out of scrap lumber or, in a couple of cases, hollow sections of a black gum tree which explains the name of the trap. Grandpa Joe showed me how to craft a simple trigger-and-drop-door mechanism. Again, I wasn’t particularly successful, but it got me in the fields and kept me out of mischief.

Trapping was a daylight activity though, checking the line, resetting or moving traps as I saw fit, and carrying anything in the way of a catch home or to a friend’s place for skinning. The remaining hours in free days would be devoted to wandering, wondering, and walking a number of miles which would be beyond me today. I always had a gun in hand and sometimes our beagles along as companions. Often though I was alone, devoid of even canine companionship, and once out of sight of houses and the sounds of town it was easy to imagine I was back of beyond. More often than not I’d bag a rabbit or two, maybe get a bushytail, and on rare occasions a grouse or quail. Seldom indeed did I head home in the gloaming without heft of some kind in the game bag of my old Duxbak hunting coat.

An integral and important part of those carefree days of boyhood adventure, not only when alone but when groups of us headed out on Saturday for an all-day rabbit hunt, focused on food. Like most active teenagers, I was a trencherman of no mean ability, and the aforementioned Duxbak jacket, whatever it carried at day’s end, always held plenty of food at the start of an outing. Sandwiches featuring whatever was available—leftover chicken, meatloaf, country ham, fried eggs and baloney, peanut butter and jelly—were standard. So was a tin of Vienna sausages or sardines, with a sleeve of soda crackers to accompany them. By the way, for me at least it’s passing strange how Viennas and sardines taste like the finest of fare when consumed outdoors. Often there would be a chunk of cornbread, and a small raw onion or turnip went just fine with it. Another favorite was a cold sweet potato. Add a couple of apples from Dad’s small orchard, still crisp and sweet thanks to cool storage in the basement; maybe an orange; some Chinese chestnuts from our tree or store-bought nuts left from Christmas; and all that remained necessary to ward off any hints of peckishness were treats for the sweet tooth—and did I ever have one (still do, for that matter).

My two favorites, and it would have been a tossup as to which I preferred, were homemade fried pies and hefty slices of Mom’s apple sauce cake. Usually one or the other was available, at least early in January when the blessings of Christmas bounty had not been exhausted. Fruit cake was another choice, because invariably Daddy had one or two given to him each year. Throw in assorted cookies, orange slice cake, hard candy, leftover holiday gum drops, and the like, and I had all that a greedy-gut boy could want for a field lunch or a mid-afternoon sugar boost. Occasionally I would carry a thermos of milk or hot chocolate, but far more often I just drank from a spring or branch. Both were available pretty much everywhere you turned in the Smokies, and in those days I didn’t even know what giardia was, much less worry about it.

Another standard January activity, and one I look back on with great fondness, involved listening to the radio on Saturday and Sunday evenings. We didn’t have a television (almost certainly that was a blessing), but the entire family would listen to some of the popular radio shows of the day. I particularly remember Amos and Andy (which would never pass political correctness muster in today’s world), Gunsmoke, Gene Autry, the Arthur Godfrey Show, Death Valley Days, the Grand Ole Opry, and the Wayne Raney Show on WCKY out of Cincinnati. We also listened faithfully to North Carolina basketball in the glory days of Lenny Rosenbluth and, a few years later, the Kangaroo Kid, Billy Cunningham. I guess that in some ways I haven’t changed all that much, because these words are being typed while a CD of the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band plays.

Cracked black walnut ready for picking.

Often while we were listening to the radio, there would also be an intense session of picking walnut meats. The nuts would have been gathered back in late October or November, allowed to dry and cure so that the husks could be easily removed, and at some point Daddy would spend a few hours cracking them atop an anvil. Everyone pitched in to get the meats, and as anyone who has ever dealt with walnuts knows, it is a chore requiring considerable patience and care. In the end though, the rewards were well worth it. Mom used the nuts in all sorts of baking. Her chocolate chip-and-walnut cookies, when still warm from the oven and served with a tall glass of milk, were pure Nirvana. The nuts also went into her version of Waldorf salad, applesauce and orange slice cakes, banana nut bread, date-walnut bars, and a host of other treats.

I must pause at this point to note that the wife of a loyal reader who lives nearby, Rob Williams, “gifted” me with a whole applesauce cake between Thanksgiving and Christmas. Talk about scrumptious! I immediately violated Momma’s cardinal rule about never cutting an applesauce cake until it had had a couple of weeks to soak up periodic applications of apple cider and had me a slice for supper. Subsequent slices disappeared like autumn leaves blown away in the face of a strong front, but for a couple of weeks I was living in culinary high cotton.

Thoughts of all those fun times and fine food lead me to the conclusion of this month’s musings in the form of some thoughts on New Year’s and the departure of 2020. It wasn’t a good year for me—all the COVID-19 mess, the loss of my partner for 53 years, increasing awareness of the fact I’m a great distance physically and chronologically from the days I so fondly recall in these newsletters, and a political world gone to hell.

Toms Branch feeds Deep Creek in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park just a few hundred yards from the trailhead for the stream.

Enough of that though. I refuse to feel sorry for myself or carp much about fickle fate. Instead, I’ll take Grandpa Joe’s route, which invariably involved optimism even when he was suffering from the “miseries,” and ponder pleasant matters. For example, I’d rather think about New Year’s as it has traditionally been celebrated in the North Carolina high country of my boyhood. Pretty much as is true everywhere, mountain folks welcomed the New Year with celebration, resolutions, consumption of special foods, and a variety of outdoor activities. Some aspects of mountain New Year’s traditions—jumping anvils and “first footing,” for example–belong to a world we have largely lost. Others endure, especially back in the steep hills and deep hollows where folks hold tenaciously to time-honored practices.

In my family, New Year’s Day was celebrated in two ways—by a day of hunting followed by consumption of a special meal in the evening. None of us stayed up until midnight to bid farewell to one year and hail the arrival of the next—such late hours don’t lend themselves to an old-fashioned, all-day mixed bag hunt beginning at daylight. On the other hand, at day’s end on January 1, wonderfully tired, we were primed to consume the fare of the season lovingly prepared by Mom.

There was really nothing special about New Year’s Day hunts other than the date. After all, we had been doing pretty much the same thing every Saturday since rabbit season opened. Once we took to the field—a bunch of hunters and enough beagles to make the ridges ring with joyous sounds when they were hot on a cottontail’s trail—there were all sorts of possibilities. To be sure we bagged rabbits, with the normal total for the party invariably reaching double figures. Cottontails were far more plentiful in the mountains then than is the case today. We frequently flushed coveys of quail, and when that occurred there would be a veritable barrage of shots.

These covey rises, what one great upland game writer once described as “a heart stopping explosion,” usually occurred as we walked through fields of broom sedge and briars trying to jump a rabbit. Similarly, if a grouse got up it would draw fire, although those drummers of the woods have an uncanny knack of putting obstacles between you and them when they take flight. Throw in the occasional woodcock or a squirrel which had the misfortune to be spotted high up in a walnut or oak tree, and you had the makings of a true mixed bag.

Those cottontails and bushytails, along with quail and grouse, made wonderful table fare and we often dined on game. When it came to New Year’s Day, however, four menu items were standards in most households of our acquaintance. One of them, cornbread, was standard daily fare. The dishes were black-eyed peas, backbones-and-ribs (we ate that instead of hog jowls), and either turnip or mustard greens. Many folks, and both Mom and Grandpa Joe certainly belonged to their ranks, believed you were courting a year-long run of bad luck, if not flat-out disaster, should you fail to eat those dishes or close approximations of them on New Year’s Day.

On the other hand, consuming those dishes assured good health, good luck, and a year of prosperity—the pork for health, the black-eyed peas for luck, and the greens for greenbacks in the pocket. The good fortune may or may not have been the case (we certainly missed the boat in terms of money, but I now know that I built up a much more significant fortune in the form of accumulated experiences). This holy triumvirate of foodstuffs was invariably joined by a fourth item—cracklin’ cornbread. Indeed, there was pork everywhere you turned. Hog jowl or backbones-and-ribs (if you’ve never sucked the marrow from a rib you’ve missed a culinary treat), greens which were always cooked with streaked meat, the peas featured streaked meat as well, and then there were the cracklin’s. Altogether enough cholesterol to clog a whole cluster of arteries, but my, was it fine fare.

Along with the food customs, there were other traditions related to January 1. Several were connected with fireplaces. In some homes a Yule log would have been smoldering since Christmas. It was time for it to finish burning, although some tried to “hold” it until the arrival of Old Christmas on January 6. One way to speed up the burning, other than moving the remnants of the log well into the middle of the hearth instead of having it at the back, was to burn the family Christmas tree limb by limb. The aroma of cedar, pine, spruce, or hemlock would fill the house with a fragrance which welcomed the New Year.

Long ago empty muzzleloaders would be fired up chimneys to “serenade” January 1. More often though, the serenading took place outdoors, with guns being fired in the air as burnt black powder wafted through the air and wreathed celebrants. Muzzleloaders also figured in turkey shoots and other competitions as well, and there was general noise-making in the form of anvil shooting or stump blasting. Both involved filling a hole (there was normally one in old-time anvils and a couple of minutes work with an augur did the trick on a stump or tree) with powder and setting off. The resulting noise rumbled like a cannon. All this commotion has been replaced by fireworks in today’s world, although there may still be places in the high country where firing guns into the air is a way of welcoming a New Year. We didn’t do any of that shooting. In Daddy’s eyes it would have been a shameful waste of ammunition and, besides, we got plenty of shooting done while out hunting.

Times change and probably not one mountain family in a dozen, or for that matter, a similar ratio of those in other parts of the country, likely enjoyed traditional fare come January 1. Shootin’ matches and powder burnin’s have become scarce as hen’s teeth. Still, it seems appropriate at least to give a token nostalgic nod to a world of vanishing folkways and food ways. For my part, I intend to cling to that vanishing world as best I can.

I’ll just close by wishing each and every one of you all the best for 2021. Thanks for being readers, and let me assure you that the comments which reach me each month after this newsletter’s appearance mean a great deal. Indeed, they are a major stimulus and remind me that maybe, just maybe, my efforts have some meaning to others.

***********************************************************************************

JIM’S DOINGS

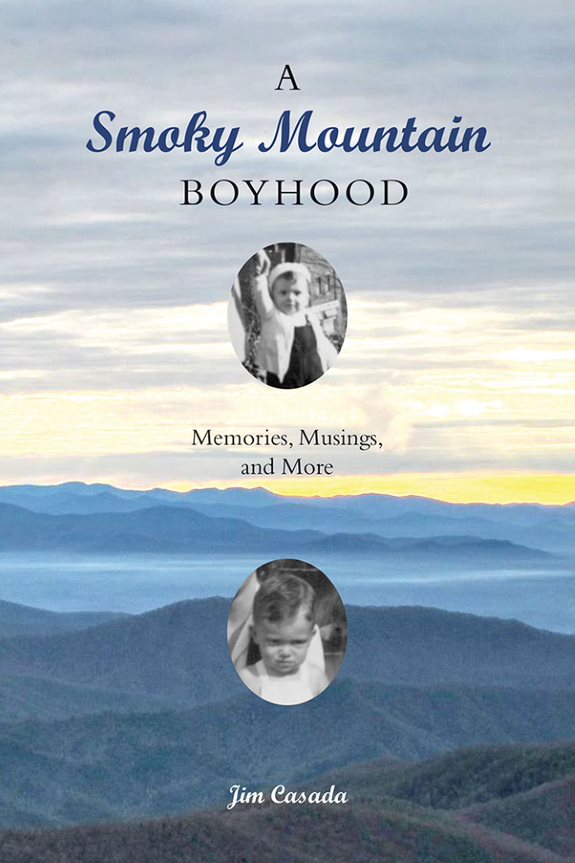

Much of my time over the last month has focused on promoting my new book, A Smoky Mountain Boyhood: Memories, Musings, and More. I’m happy to report that sales have been going reasonably well, and heartfelt thanks to those of you who have bought the book. My brother, Don, says it is the best thing I have done. I can’t make a meaningful evaluation, but I can assure every page comes from the heart. I also want to make a couple of pleas to you as readers.

First, if you haven’t already done so, I hope you’ll give serious consideration to acquiring the book, and it is front and center on my website with all the necessary ordering information. Secondly, although I much prefer orders directly from me as opposed to Amazon, Barnes & Noble, or other Internet book sites, folks who know a lot more about such things than I do tell me that favorable reader evaluations on such sites are a big plus. With that in mind, if you’d take a few moments to go to Amazon and give me a rating I’d be most appreciative.

I do a lot of reading all the time, but that’s especially true in what Grandpa Joe used to refer to as the “mollygrubs and miseries” season, the time of year when cabin fever sets in. That’s been the case of late. Another major effort has been connected with what I hope will be my next book. Its working title is “Mountain Fixin’s: A Smokies Food Memoir.” I’ve finished the manuscript and have a publisher giving it a close look, so wish me good luck and if you’d be interested in eventually adding it to your library, by all means let me know.

Then there are the usual activities which form a pretty steady part of my life—my weekly column for the newspaper in Bryson City where I grew up, the Smoky Mountain Times; the occasional piece for “Sporting Classics Daily,” the daily blog by the magazine of that title; my book column for the actual magazine (I’ll also have a feature story on a grand turkey mystery involving murder in the next issue of Sporting Classics); regular contributions to Smoky Mountain Living and Carolina Mountain Life; frequent stories for that wonderful state magazine, South Carolina Wildlife; and most recently connection with and a number of assignments for Columbia Metropolitan Magazine.

Finally, I’ve agreed to do two books for the book-publishing arm of Sporting Classics. One will be a volume I edit and compile involving great turkey hunting stories. It will follow the same general approach as two previous efforts of this type, The Greatest Quail Hunting Book Ever and The Greatest Deer Hunting Book Ever. By the way, I didn’t choose the titles, but they do contain a lot of great stories no matter the quality of work performed by the guy (me) who edited and compiled them. Both are available through my website. The second will be a series of original profiles of noted African hunters, a subject I’ve long studied, accompanied by a story from their own accounts of adventures afield. In short, I’ve got plenty to keep me busy.

*************************************************************************************

THE LIGHTER SIDE

NIGHT CRAWLER FISHING

I’ve shared humorous stories associated with Britt McCracken, a grand figure from my youth, in previous newsletters. He was, without question, the funniest man I have ever known. If ever there was a natural comic it was Britt, and no small part of his ability to keep everyone in stitches revolved around the fact that he was exceptionally quick witted. No matter what the situation, he seemed to have an answer, a quip, or a perspective which came to him instantaneously. Such was the case when Britt had an unwelcome encounter with a game warden during a fishing trip in Georgia.

McCracken was fishing a trout stream where only single-hook artificials, either a fly or a spinner, were permissible. He stayed within the dictates of the regulations for an hour or so, but having caught no fish soon decided he need to offer something a bit more tempting. Having anticipated just such a situation, he resorted to a stash of night crawlers he had hidden in his vest and tipped his spinner with one of them. Things picked up immediately, and within a short time he had two or three trout in his creel.

The he happened to look up and saw a game warden headed his way on a trail paralleling the creek. Britt immediately began jerking his rod tip vigorously, an action which would normally remove the illegal bait. However, this time he had apparently hooked the night crawler too well because it resisted all his efforts until the warden was standing beside him. Caught in the act, Britt greeted the warden cheerily, reeled in his spinner adorned with a night crawler, and shook his head as if mightily puzzled. “I’ll be damned,” he said. “I’ve caught red horse, knottyheads, hog suckers, and even a hellbender on a spinner, but that’s the first time I ever had a night crawler hit one.” The warden was so amused with this explanation he let Britt off with a warning.

*******************************************************************************

COOKING CORNER

MUSTARD GREENS AND TURNIPS

Wash a big bait of greens fresh from the garden, being sure to give them multiple rinses to remove all dirt and grit. If they are overly large, it is best to remove the stems. Chop up two or three turnips in small pieces (diced is best). Place both in a large pot with plenty of water. Throw in a couple of slices of streaked meat (called fatback or side meat in some parts of the country) and bring to a boil. Reduce to a simmer and allow to cook until greens and turnips are done. Add salt to taste. Serve piping hot. Be sure to save the pot liquor. It makes for mighty fine eating when you dip a chunk of cornbread in it or, as Grandpa Joe used to do, pour it in a bowl and crumble cornbread over the rich, vitamin-filled juice. Turnip greens can also be cooked this way, but my personal preference is for mustard. Collards are the green of choice here in South Carolina where I now live, but you can have my part of them.

BACKBONES-AND-RIBS

A crockpot with backbones and ribs ready for the table.

Unless you know a butcher and can get him to custom cut for you, don’t count on finding this New Year’s staple on grocery shelves. You can find ribs, but invariably they have been cut away from the backbone. That’s too bad, because the bits of meat where the ribs meet the backbone give credence to the old adage “the closer to the bone, the sweeter the meat.” If you obtain only ribs, be sure to get the entire bone, for the end where the rib meets the backbone will soften in cooking and provide tasty marrow to suck. Cooking backbones-and-ribs, or whatever cuts of pork you manage to obtain as the closest possible substitute, is the essence of simplicity. Trim off excess fat, place in a crockpot with a bit of water, and slow cook for several hours. With the addition of salt and pepper to taste, you have some simple stuff fit for a king. If you have leftovers, chop up the meat, add your favorite barbeque sauce, and you’ve got the makin’s of fine BBQ sandwiches.

CROWDER PEAS

I’ve never known for sure what the “proper” name for these members of the legume family is. In my family we variously called them field peas, crowder peas, and clay peas. In other areas I’ve heard them described as zip peas or purple hulls (although the variety we grew didn’t have the distinctive tinge of purple pods when the peas were mature). They come in literally dozens of varieties but all share a couple of things in common—they produce prolifically and are delicious to eat. For years I normally shelled and froze thirty quarts or so, although these days I give most of the crop away as it comes in. I am partial to cooking them with streaked meat (anyone who grew up in the mountains will tell you that pork will dress up and improve the taste of most anything). Just cook in a sauce pan until done and, if you happen to be a fan of chowchow as I am, top them with it. Otherwise, just enjoy them with cornbread.

HOPPIN’ JOHN

I never heard of Hoppin’ John growing up, but was I began studying the writings of Archibald Rutledge in detail along with paying serious attention to South Carolina Low Country culinary traditions, I was exposed to mention of the dish on a regular basis. It has long been a traditional Palmetto New Year’s dish, and since it is as scrumptious as it is simple to prepare, I’m including a recipe for it here.

1 cup rice

Small chunk of bacon or fatback

1 medium onion

Salt and pepper to taste

1 cup black-eyed peas (dry)

Sliced bacon

Soak peas overnight then cook in slightly salted water with a chunk of fatback. When the peas are done, cook rice in a steamer with minced onions and sliced bacon which has already been fried separately. Add the liquid the peas were cooked in along with the peas. Add a bit of additional water if needed. Stir gently and add salt and pepper to taste. I might note that this recipe, along with a few dozen others, form the final chapter in a work I edited, Carolina Christmas: Archibald Rutledge’s Enduring Holiday Stories (available through my website for $29.95). All the recipes have a holiday focus and they are original—Rutledge mentioned them in his writings but Ann and I put together and tested the actual recipes.