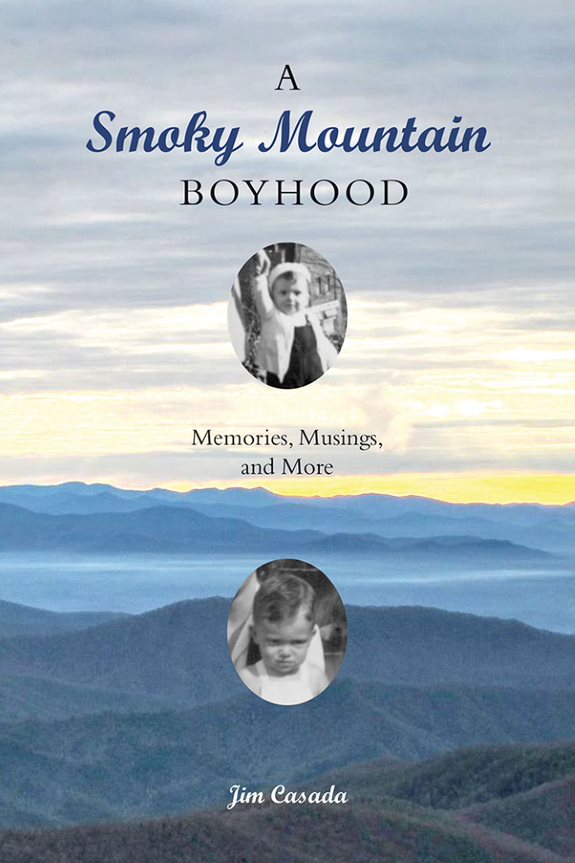

Jim Casada’s latest book, A Smoky Mountain Boyhood: Musings, Memories, and More has just been published by the University of Tennessee Press. The work encompasses 41 chapters and spans 300+ pages as well as including an extensive section of vintage photographs. Part autobiographical, it is primarily a window into the world of the middle of the 20th century as the author knew it growing up in his beloved highland homeland.

A publisher’s blurb for the book states that “in A Smoky Mountain Boyhood Casada pairs his gift for storytelling and his training as a historian to produce a highly readable memoir of mountain life, with stories evoking a strong sense of place and reflecting richly on the traits that make the people of Southern Appalachia a unique American demographic. Containing a strong sense of adventure, nostalgic tone, and well-paced prose, Casada’s book will be appreciated by those yearning to rediscover their childhoods or imaginatively climb these mountains.”

Divided into four sections—“High Country Holiday Tales and Traditions;” “Seasons of the Smokies;” “Tools, Toys, and Boyhood Treasures;” and “Precious Memories”—each of the book’s parts reflect on a memorable coming-of-age in the Smokies. Among the work’s focal points are traditional folkways; hunting and fishing; growing, preparing, gathering and eating wide varieties of foodstuffs; and the overall fabric of mountain life in yesteryear.

The full table of contents and a sample chapter appear below. Copies of the book are $29.95 plus $5 shipping and handling (Jim Casada, 1250 Yorkdale Drive, Rock Hill, SC 29730). I will cover the extra postage costs if you order more than one copy, so the shipping is $5 regardless of the number of copies ordered. The book is nicely timed for the Christmas season and will make a fine gift for anyone who cherishes yesteryear, enjoys storytelling, or wants to take a longing look backward into the magical world of a mountain boyhood.

************************************************************************************

A SMOKIES BOYHOOD AND BEYOND:

MOUNTAIN MEMORIES AND MUSINGS

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DEDICATION

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

GLOSSARY

INTRODUCTION

PART I–HIGH COUNTRY HOLIDAY TALES AND TRADITIONS

CHAPTER 1—NEW YEAR’S

CHAPTER 2—DECORATION DAY DOIN’S

CHAPTER 3—MOTHER’S DAY

CHAPTER 4—FATHER’S DAY

CHAPTER 5—FAMILY REUNIONS

CHAPTER 6—HOMECOMING

CHAPTER 7—REVIVALS

CHAPTER 8—THANKSGIVING

CHAPTER 9—OLD-TIME NATURAL CHRISTMAS

CHAPTER 10—MOMMA AND THE SPIRIT OF CHRISTMAS

CHAPTER 11—CHRISTMAS HEARTBREAK

PART II—SEASONS OF THE SMOKIES

CHAPTER 12—A LAND OF DELIGHTFUL VARIETY

CHAPTER 13—WEATHER WISDOM

CHAPTER 14—SMOKY MOUNTAIN RAIN

CHAPTER 15—MUSINGS ON THE MONTHS

PART III—TOOLS, TOYS, AND BOYHOOD TREASURES

CHAPTER 16—SIMPLE CHILDHOOD PLEASURES FROM YESTERYEAR

CHAPTER 17—MEMORIES OF MARBLES

CHAPTER 18—A PASSION FOR POCKET KNIVES

CHAPTER 19—SLING SHOT MEMORIES

CHAPTER 20—DAISY DAYS: BOYS AND BB GUNS

CHAPTER 21—FIRST GUN

CHAPTER 22—CANE POLE EXPERIENCES

CHAPTER 23—A FASCINATION WITH FLY RODDING

PART IV—PRECIOUS MEMORIES

CHAPTER 24—HAS THE STOCK RUN OUT?

CHAPTER 25—OF SEEDS, SOWING, AND OLD-TIME SURVIVAL TECHNIQUES

CHAPTER 26—THE ENDURING RITES OF SPRING RENEWAL: A GARDENER LOOKS BACK

CHAPTER 27—PICKIN’

CHAPTER 28—HOT SUMMER DAYS AND COLD WATERMELON WAYS

CHAPTER 29—THE AMERICAN CHESTNUT: SAGA OF A FALLEN MONARCH

CHAPTER 30—THE JOYS OF NUTTING

CHAPTER 31—SCHOOL DAYS

CHAPTER 32—THE LORDS OF LOAFER’S GLORY

CHAPTER 33—TOWN SQUARE BIBLE THUMPERS

CHAPTER 34—DID YOU EVER? VANISHING ASPECTS OF THE MOUNTAIN SCENE

CHAPTER 35—TALE OF AN OLD COFFEE CUP

CHAPTER 36—THE ANGEL OF BRASSTOWN

CHAPTER 37—A DAY AT DEVIL’S DIP

CHAPTER 38—OF AN OLD MAN, HOG FEEDING, AND LESSONS LEARNED

CHAPTER 39—IN PRAISE OF PORCHES

CHAPTER 40—REMEMBERING GRANDPA JOE

CHAPTER 41–BORN STUBBORN: MUSINGS ON TRADITIONAL MOUNTAIN

CHARACTER TRAITS

**********************************************************************************

BIBLE THUMPERS

During warm weather months in the Smokies of my youth, itinerant preachers were fixtures on town squares throughout the region. Virtually all their preaching was done on Saturdays. On that day their potential audience grew considerably. It was “come to town day” when rural folks did their shopping, bought their groceries, got garden plants and animal feed at the local Farmer’s Federation or whatever cooperative served their region, and simply enjoyed the opportunity to be out and about. During the summer there would likely be a goodly sprinkling of goggle-eyed tourists, awestruck by this local eccentricity of religious celebration, as well.

These wandering purveyors of the Gospel were universally known as “Bible thumpers,” thanks to one of a number of tactics they employed to gather an audience and then keep its attention. They carried a massive Bible and would, with some regularity, raise it aloft with one hand then give it a resounding thump with the other. The best of them could deliver a whack which made a Bible pop like an exploding firecracker.

In my personal experience wandering preachers seldom if ever mentioned a particular denomination and probably did not belong to one. Few if any were ordained other than that they had decided, on their own, to answer a calling. They were strangers to formal theological training, had likely never darkened the doors of a seminary or Bible college, and were in many ways elusive figures. No one seemed to know their origins (I never knew a Bible thumper who lived locally) and seemed, at least in my youthful eyes, men of great mystery.

Their uncertain backgrounds and lack of formal credentials notwithstanding, all possessed salient characteristics, and the best of them were amazingly persuasive. To a man, although they would likely have given anyone mentioning the phrase “stage presence” a blank stare, they instinctively understood the concept. Let one of the more passionate among their ranks really get down to business and he was something to behold. Along with periodic hammering of his primary prop, a Bible, there would be mesmerizing gesticulation to punctuate or emphasize particular points, spittle would fly as verses were spouted, and wayward human behavior invariably formed a critical part of the subject matter.

The finest of the street preachers had a certain rhythm to their delivery, with the phrase “Let me tell you brother” being repeated countless times. It would almost always be followed by a mighty smack of the Bible and an utterance (I’m not sure it was a word) which sounded to me like “Huh!” or “Ha!” There were periodic pauses to wipe the sweat from their brow with large handkerchiefs and the overall level of showmanship rivaled that of a carnival barker or purveyor of patent medicine. There was never any question of a speaking permit, impeding traffic, or anything like that. The verbal offerings were variously viewed as serious religion, welcome entertainment, and sometimes an opportunity to debate religious issues.

I must confess that I don’t recall a great deal about doctrinal discussion or the text of sermons these preachers offered, and even if I could it’s likely thematic coherence wouldn’t have been a strong point. But those from the Bible thumper ranks who garnered large crowds and keen listeners had a definite proclivity for the “hellfire-and-brimstone” school of delivery. A skilled thumper could paint verbal visions of Hades and word portraits of Satan sufficient to scare the bejeebers out of a small boy. You could almost smell sulfur and feel heat as they ran through a litany of sins serving as a guaranteed passport to the portals of the underworld. Interestingly, I recall almost no references to good works and ways to enter paradise. Devilish deeds and damnation, along with myriad examples of sinful shenanigans, were standard fare on the square.

Never mind that Swain was a dry county at the time, as were most others in the Smokies on both the North Carolina and Tennessee sides, alcohol topped the lengthy list of sins the thumpers would enumerate. Many of these itinerant peddlers of the Gospel had a colorful array of descriptions for intoxicants—John Barleycorn, tanglefoot, golden moonbeam, demon rum, stump water, squeezin’s, and devil’s brew were among them. They would rail about ruined homes, abused wives, ill-fed and poorly clothed children, general slovenliness, and more in association with vile drink.

Some weighed in heavily on the evils of tobacco as well, but that didn’t go over particularly well with the benchwarmers of Loafers Glory, for almost to a man they either smoked or chewed tobacco. When the subject matter turned to that “vile, stinking weed,” there would be audible grumbling and rolling of eyes in the audience. Many years later I would learn that during the early seventeenth century, especially in the reign of King James I, similar fulminations regarding tobacco were standard fare. Had the Bible thumpers known of Robert Burton’s characterization of the plant in The Anatomy of Melancholy—“’Tis a plague, a mischief, a violent purger of goods, lands, health: hellish, devilish, and damned tobacco, the ruin and overthrow of body and soul!”—they would surely have quoted him. As it was, this particular lamentation was pretty much a non-starter, for not only was the primary audience addicted; many of them or their kinfolk grew burley tobacco as a cash crop.

On the other hand, titillating tales of lust, chastising of chasers of women, and condemnations of adultery played exceptionally well with audiences. Dancing was another frequent target. It was a social activity inviting all sorts of lurid descriptions, although the best I ever heard was in a class by itself. One particularly articulate preacher excoriated any and all dancing at considerable length, concluding with a thunderous statement that it was nothing more or less than “a vertical position for horizontal desires.”

Flashy or revealing attire—anything from Bermuda shorts to ladies wearing fashionable slacks, from penny loafers to pegged pants—provided fine verbal fodder. But my favorite moments came when some particularly daring or devoted thumper, lacking any verbal filter or acquaintance with diplomacy, took it on himself to start pointing fingers. He would single out some hapless passerby as a specific example of a soul whose evil ways were made manifest by their manner of dress and hector that individual in merciless fashion.

The Loafers Glory crowd, ever alert to an opportunity for comic relief or perhaps conversational meat for the coming week, often played bit roles on such occasions. It was interactive theater, so popular in England during the Elizabethan era, brought to the mid-20th century. No sooner would a preacher direct his attention to someone who seconds before had been sauntering innocently down the sidewalk than he would get support known as “aggin’ and hissin’.” Cries of “You tell ‘em, brother;” “Preach on preacher;” “Tell it all brother, tell it all;”or just heartfelt “Amen” would ring out from the audience.

More often than not those individuals who drew such unwelcome attention slunk along the sidewalk in shame, but on one memorable occasion a local woman noted for her outspokenness and eccentric behavior turned the tables in dramatic fashion. She always carried an umbrella, and when the thumper directed shaming comments at her, that parasol instantly turned into a weapon. Carrying it before her like a soldier charging with a bayonet-equipped rifle, she marched up to the offending preacher and accosted him. Emphasizing every word with threatening pokes of her weapon, she unleashed some decidedly unladylike language, called the itinerant a “sanctimonious son of a bitch,” and threatened to beat him to the ground. The hapless fellow, used to having the upper hand, was caught on the horns of a dilemma. He could hardly take physical measures with a woman, and it was abundantly clear she had no intention of leaving or ceasing her frontal assault. After perhaps 30 seconds of being the target of withering abuse, he ignominiously fled the scene to the accompaniment of laughter and applause from the Loafers Glory contingent.

Other than this single instance, I don’t ever recall any verbal counterattacks aimed at the street preachers. However, old men in the audience felt perfectly comfortable in shaking their heads in disagreement or in suggesting to someone sitting next to them that the Bible thumper was venturing into questionable religious territory. Similarly, a real stem-winder of a preacher expected and received plenty of positive responses with knowing nods or along the lines of “I hear you, brother.”

Confrontational tactics were standard among the thumpers, and this method of conveying the Gospel message found widespread usage throughout Smokies churches as well as on the streets. A cherished, oft-told tale from my family’s own store of lore involves a great-grandfather who was a fire-and-brimstone Baptist. A relatively young man in his community notorious for his carousing lifestyle died unexpectedly, and his family asked my ancestor to handle the memorial service. He tried to beg off, frankly mentioning the well-known sinfulness of the deceased, but the family was insistent that he was the man to handle the funeral.

He eventually relented, agreed to preach, and the first portion of the service went smoothly enough. The congregation sang a hymn or two, there were readings from Scripture, and then Rev. Casada got down to serious business. Looking down from the pulpit to the open casket situated just a few feet away, he pointed at the deceased and pronounced: “There lies one who has gone to Hell!” That shocking statement was immediately followed by him turning to the family seated in the front rows of the little country church and shaking a finger at them with the admonition: “And there sits a bunch more traveling down the same road unless they change their ways.” Oral tradition does not provide details of what happened next. But since other members of the family from that general time period appear in court records for affray, and given the clan’s notoriety for tempestuousness, it probably wasn’t a placid scene.

Curiously, with the notable exception of the umbrella-toting lady, I don’t recall women ever paying much attention to the thumpers. They would walk by a street preacher while going about their business without much more than casting a glimpse in his direction, if that. On the other hand, old men with nothing better to do, and young boys en route to the Saturday matinee at the nearby Gem Theatre, were prime candidates for a captive audience. More than one of the Bible thumpers railed against the evils of movies, although I don’t think it had any impact whatsoever. I know that personally my dime (later twelve cents when the price for enjoyment of a fine Western, a cartoon, a serial, and a fine Western went up) always got spent, and there was never a street preacher of sufficient quality to make me miss a movie.

Still, these wandering purveyors of the Word were an integral and interesting, though not necessarily important, part of the Saturday scene in Bryson City as it was in the years between the end of World War II and sometime in the 1960s. Friends from that era who grew up elsewhere tell me they were a common local feature throughout the Smokies. As the Age of Aquarius arrived, Bible thumpers disappeared from the mountain scene. Their day in the sun had come and gone, but for at least two generations they brought color, entertainment, and a particular brand of fervid religious outlook to the high country scene.