FOND DECEMBER MEMORIES

Given an hour or two to ponder matters, I’m confident I could come up with at least a couple dozen memories from my Smoky Mountain boyhood connected with the Christmas season. There are food memories aplenty (a small sample of recipes appears below), recollections of playing outdoors on those occasions we got a good snow, times spent at church or with family, lots of hunting, and of course memorable gifts. In the latter category my first BB gun and my first “real” gun (a Stevens Model 220A 20 gauge shotgun I still own), various items of Duxbak clothing, and books to address my boundless appetite for reading material, all jump out as welcome vestiges of a now distant past.

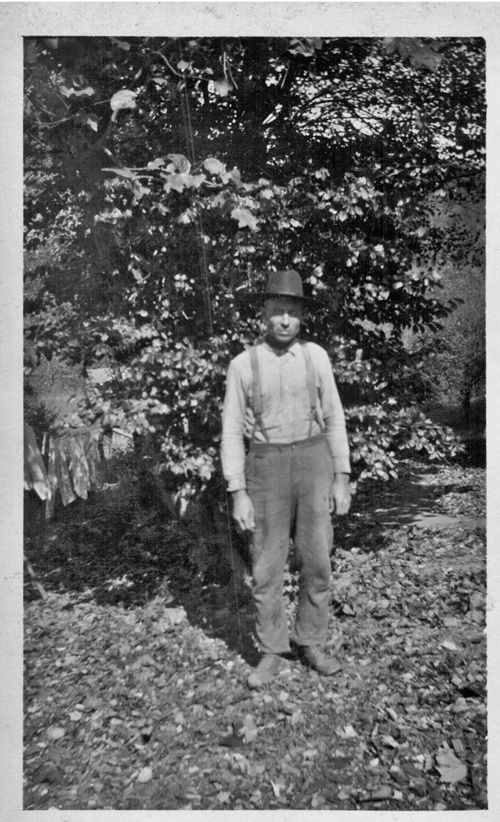

Grandpa Joe Casada in his middle years, already showing signs of a hard life

Then there are fond recollections of Grandpa Joe, poor as Job’s turkey, somehow managing to get a small item for each of his many grandchildren; Grandma Minnie’s apple stack cake; Aunt Emma’s orange slice cake; baked free-range chickens and festive meals with the extended family; Grandpa Joe’s palpable pleasure at a big box of Apple Twist Dry Chew tobacco Daddy always got him; church pageants, lots of visitors; caroling; folks showing up unexpectedly and offering a hearty “Christmas gift” when you came to the door; Mom’s aptitude for decorating; the year my sister, a gifted seamstress, made me a Nehru jacket; and much more.

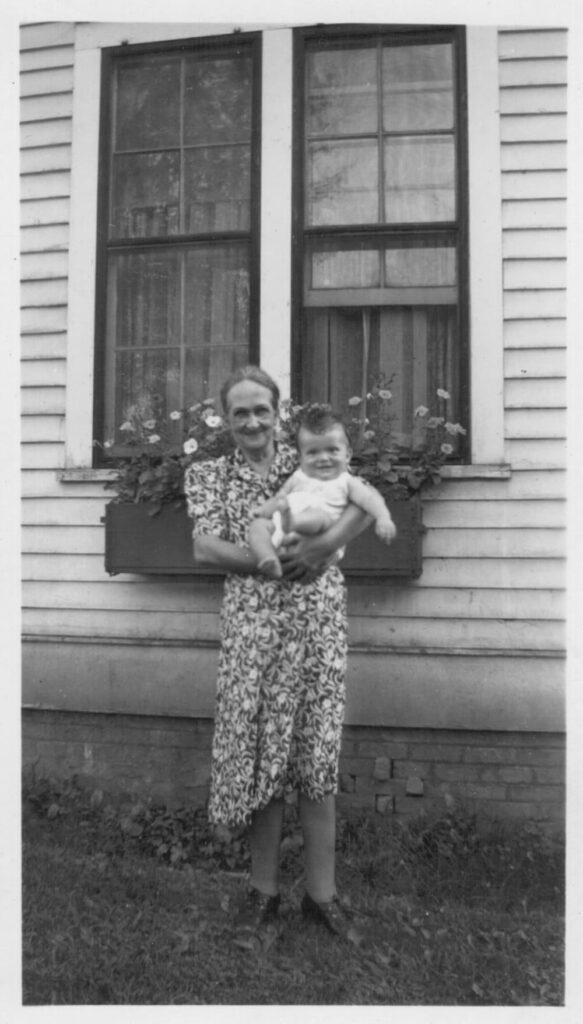

Grandma Minnie Casada with me as an infant

But two tales connected with Christmas stand out above all others, each of them focuses on one of my parents, and I thought sharing them, pretty much in the form I’ve already done in magazine or newspaper articles over the years, might be appropriate. Here they are, and I think you’ll agree, after reading them, that I was greatly blessed in the nature and outlook of my parents.

****************************************************************************

MOMMA AND THE SPIRIT OF CHRISTMAS

Momma and Sarah (her youngest granddaughter) at Christmas, 1993.

The joy in Mom’s eyes at the opening of a gift is obvious.

If the spirit of Christmas embraces things such as love of family, togetherness, warm feelings, goodness, excitement, and faith, then my mother was the quintessence of that spirit. Adjectives aplenty come to mind when thinking about her love of life in general as well as the Yuletide season in particular, but none is more fitting that the word merry. She always had a sparkle in her eyes, breathless excitement in her being for even the most ordinary of undertakings, and a constant joie de vivre. She was merriment personified.

Momma had a troubled childhood. Born in the lovely high country of North Carolina, she spent most of her youth far from her native heath. Her mother died when she was just beyond infancy, and her father apparently decided it would be best if relatives raised Mom. Her adoptive parents moved frequently, and it was always my impression that the resulting instability affected her a great deal. Certainly once she was married and settled in a home stability was something she cherished. My father loved to relate the story of how, shortly after they married and bought the home that is still in the family, she told him: “I never want to move again.” Until the final months of her life, when Parkinson’s disease and dementia necessitated her residence in a nursing home, her desire was fulfilled.

Although Momma never said much about it, and certainly the care and devotion she lavished on her adoptive parents in their later years would have suggested otherwise, clearly warmth and love were scarce commodities in her childhood. Likewise, she never had much in the way of Christmas gifts as a youngster. This was evident in two ways—the frequency with which she mentioned an elderly man who befriended her and gave her a quilt at a point when her adoptive family lived in California, and the pure delight Momma took in everything associated with Christmas.

She loved the rituals of preparing for the season, especially decorating with materials from nature. Gifted with appreciable crafting skills, at one time or another during her adulthood she made Cherokee-style baskets, knitted, crocheted, enjoyed macramé and appliqué, grew and rooted all sorts of indoor and outdoor plants, excelled at flower arrangement, was a superb seamstress, and had a real knack for decorating. Never was the latter ability on fuller display than during the Christmas season. It might be noted that Momma was exceptionally frugal, a combined product of upbringing and necessity, and all her many hobbies saved money along with providing pleasure.

She was always involved in anything and everything Christmas-connected at church—filling bags with goodies for youngsters, helping with pageants, and volunteering in any way she could. Similarly, some of my earliest Christmas memories revolve around charitable endeavors in which she strove to make sure there was some joy in the season, along with food she prepared, for those who were less fortunate. This was in keeping with her general outlook on life and her charity extended well beyond the Yuletide season. Although anything but a political creature, she had no use for food stamps, government support, and the whole tone and tenor of the welfare state. But Momma staunchly believed in helping those who needed assistance—she advocated giving a hand up, not a handout.

Then there was Christmas-related cooking, and as an endlessly hungry boy who still holds his own as a trencherman, that was of immense importance to me. Momma was a splendid cook, and one of our family’s real losses in that connection was a compulsion, late in her life, to throw away a great many things. Among the items lost to that well-intentioned but misguided mania to organize were hundreds of recipes.

Fortunately though, she had already passed many of her favorite recipes on to my wife and other family members. Among those which survived were chestnut-and-cornbread dressing; a simple yet scrumptious way to cook squirrels and rabbits; orange slice, applesauce, and black walnut cakes; pumpkin chiffon pie; cracklin’ cornbread; Russian tea; popcorn balls made with molasses; fried pies; stack cake; and homemade candies. However, if I had to pick out one dish in which her culinary skills shone brightest, it would not be associated exclusively with Yuletide, although I would hasten to add that we would invariably enjoy fried chicken at some point during the holidays.

She could fry chicken better than anyone I’ve ever known, and that included Grandma Minnie, an absolute wizard in the kitchen. I know the basics of how Momma did it—slow frying each piece that had been coated with seasoned flour after having been dipped in egg, followed by a session of the fried pieces sitting in her oven on low heat. This was standard dinner fare on Sunday, and by the time we got home from church that big skillet full of chicken would have achieved crunchy, moist, tender perfection. All of her children know the process, but duplicating the end product to a degree which matches her fried chicken has eluded us.

Momma took quiet pride in her cooking skills and loved to see her family and friends eat.

Seldom was she happier than when she could put game or fish, killed or caught by Dad or me, on the table as a main dish. It was free (that appealed to her sense of frugality) and wonderfully tasty. Throughout my boyhood, and I think precisely the same held true for both my siblings, she truly fed the multitudes in terms of setting the table for our friends. We never had much money but rest assured the Casada table exuded abundance. There was no issue whatsoever with an extra place setting or two. Interestingly, and it’s a testament to Momma’s generous, hospitable nature, my friends ate with us far more often than I ate with any of them. We were at times almost a communal kitchen for neighborhood kids.

Speaking of kids, no starry-eyed youngster with a “Christmas will never come” mindset or the firmest of believers in Santa Claus ever derived more sheer joy from receiving gifts than Momma. As much as she gave of herself, and she was tireless in that regard, she loved to open presents. Curious as a cat, for days before December 25 finally arrived she would pick up gifts bearing her name from under the tree, heft and maybe shake them a bit, then wonder aloud: “Now what that could be?” Similarly, in my mind I hear her, decades since she left us, saying with mixed disbelief and excitement when handed a gift: “Another one for me!” She was careful in opening presents, because after all, wrapping and ribbons could be recycled in the “waste not, want not” approach which was her mantra. Still, it was easy to tell she would have loved to rip the paper asunder like an eager child.

Annually, once all the presents had been opened, she would offer comments such as: “I can’t believe how lucky I am” or “This has to be the best Christmas ever.” She may not have had much of anything that was “the best” as a child, but far from looking back with regret or bitterness, as an adult she instead brought an attitude of optimism, excitement, and simple goodness to the season of Christmas.

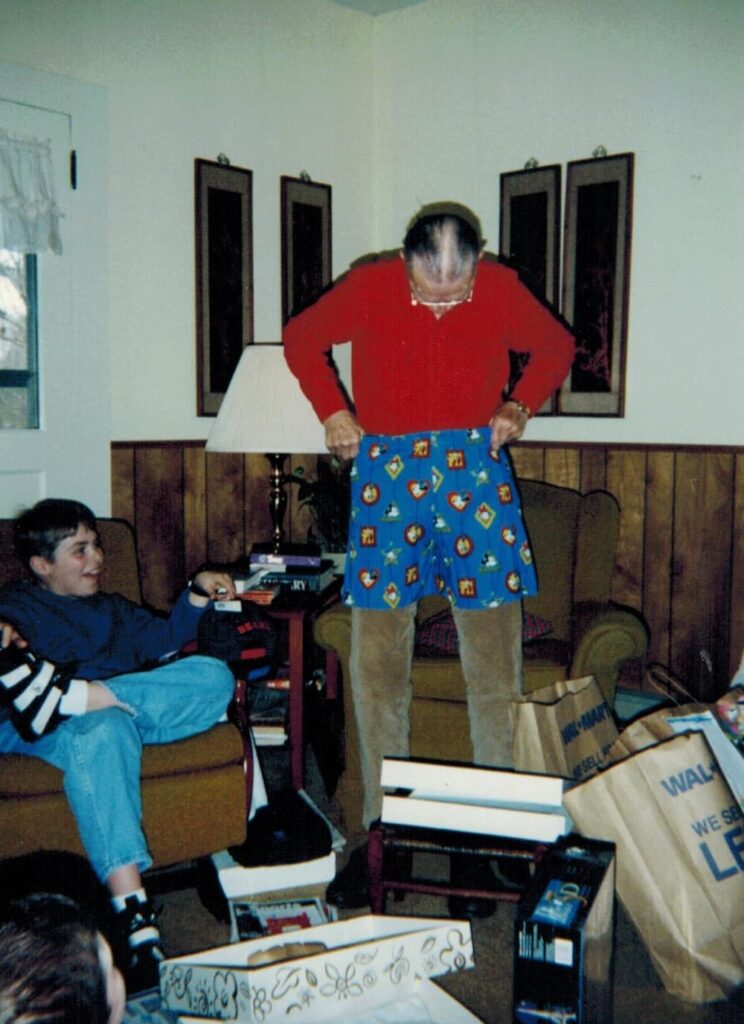

She enjoyed a good joke. There were always gag gifts in our family, and at times Momma would laugh until tears rolled when Daddy received something such as a pair of underwear adorned with images of Mickey Mouse or a Sammy Davis, Jr. audio tape (he detested that type of music). Her laughter was infectious, and even though she was the butt of jokes more than a fair share of the time, it never troubled her.

A classic case came on a Christmas late in Momma’s life when my brother and sister-in-law gave her a box of dried beans labeled “Hillbilly Bubble Bath.” As was her wont, Momma had shaken the nicely wrapped package a number of times prior to Christmas Day. The beans rattled around noisily but she couldn’t for the life of her imagine what the decorative wrapping hid. Such was her intense curiosity that when it came time to open presents she gently implored: “Can I open this box first?” When she did, with the gag gift exposed for all to see, there was a moment when, as her family convulsed in laughter, she didn’t quite realize what had happened. When the piece of mischief did dawn on Momma, her response was “Oh, shucks!” She then joined the rest of us in the magic of mirth.

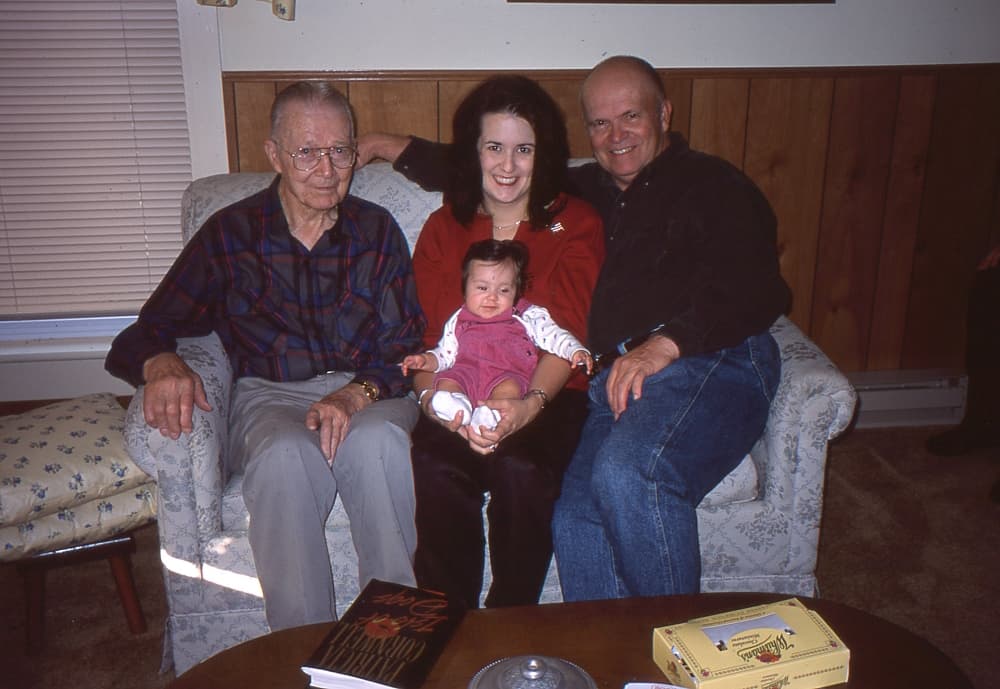

Four generations of my family–Daddy; daughter Natasha

holding her daughter, Ashlyn; and me.

As a clan, Casadas have never been exactly gifted when it comes to diplomacy, and if Momma hadn’t been a moderating influence goodness knows where her offspring might be. Daddy could be highly opinionated, and his father, my Grandpa Joe, was the essence of mule-headedness. Momma, on the other hand, always had just the right thought, action, or word when a soothing, smoothing manner was needed. She possessed a seemingly endless supply of dimes when a child did some extra work around the house, was always a soft touch when it came to providing a snack or special dish, and was game to try almost anything one of her children asked her to do. But of all the countless times she offered just the right gesture, a few words of praise, complimented my hunting prowess or fishing skills, or maybe tendered a little pat on the shoulder, the moment I remember most came at holiday time when the whole family was seated at the table.

My younger brother Don was around 16 years of age when all of us, including my wife of only a year or two, sat down to one of Momma’s toothsome meals. Midway through the feast and totally out of the blue, Don brought up a most unexpected subject. “I’ve come to a conclusion,” he pronounced. “I was born by accident.” It was undeniably true, since he came along a half generation after his siblings, but heretofore no one had dared mention the matter.

Silence reigned supreme for a seeming eternity in what has to rank as the finest example of a pregnant pause I have ever experienced. Then Momma offered the perfect response. “Yes, but you were the most wonderful accident I could ever imagine.”

That way of thinking lay at the core of Momma’s being. She was completely unselfish, genuinely moved anytime something was done for her, loving in the sort of fashion which grows in meaning over time and given reflection, and the embodiment of everything associated with the true spirit of Christmas. No one loved the season more or brought more to it in terms of warmth and a giving heart. I was blessed by having her make Christmas truly special for me over a period of some six decades. The season never comes without Momma’s remembered presence being there to escort me on whispering winds carrying haunting yet happy echoes of Yuletides of yesteryear.

Often we have enjoyed a cake—most likely one from a recipe she provided—atop a Fostoria stand she gave to my late wife. At some point during the season I make a point of re-reading some book she gave me, indicating her recognition of a budding bibliophile, as one of my gifts. My daughter will wear jewelry she passed down, my sister will recall them wrapping gifts together or sewing something for family members, and I know my brother and his wife think of her every year when they fashion a cross using materials from the wilds. It is a practice of reverence and respect for the bounty of the land Momma would have adored.

Most of all though, and it often happens at the oddest of moments and for reasons which transcend my ability to explain, I’ll think of her. Doing so will bring temporary sadness, but it will soon give way to gladness. That’s the way she would have wanted it, because Anna Lou Moore Casada was a woman and a mother who walked life’s path as a shining embodiment of the spirit of Christmas. She gave, and gave unstintingly, of herself.

**********************************************************************

CHRISTMAS HEARTBREAK

Daddy displaying a gag gift of Disney themed underwear while one of his grandsons,

Matthew, looks on in obvious mirth.

In December of 1916, hard times held the Carolinas as well as the rest of the world in a stranglehold. The Cunard Line’s R. M. S. Lusitania, the ultimate in luxurious sea travel, rested at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean. It was sunk on May 7, 1915 by a German U-Boat’s torpedo while en route from New York to Liverpool. Among the some twelve hundred souls who drowned were upwards of a hundred Americans. At that juncture shrewd observers of the international scene realized America’s entry into World War I was almost certainly in the offing, although surprisingly it did not come immediately. Pacifism and isolationism were strongly held sentiments among much of the population as well as President Woodrow Wilson. Moreover, the nation’s leaders were keenly aware of the fact that Germany had known the Lusitania carried munitions along with affluent passengers and had issued a warning that the ocean liner should not sail. Those were factors in delaying American participation.

Nonetheless, our traditional allies in Europe were stalemated in the trench warfare of the Western Front, which stretched from the English Channel to the Swiss Alps. Modern technology was bringing death and destruction on a heretofore unprecedented scale, and military leaders seem chronically unable to adjust. There was increasing awareness in Washington that the British, along with their imperial and continental allies, could not hold on indefinitely. Victory by the Central Powers was unthinkable.

A small son of the Carolina soil living on a remote hardscrabble farm at the time was blissfully unaware of ominous world affairs. Not only did he know nothing about most of Europe, along with nations across the British Empire, being at war; he had virtually no understanding of the near-desperate financial straits facing his large family. After all, there was always food on the table, simple but adequate clothing, and almost everyone the carefree lad knew lived in circumstances similar to those of his family. It is difficult to recognize poverty when you have no standards against which it can be judged.

His father, while a hard worker, was in many ways a difficult man. By nature a contrarian who could not and would not abide direct oversight by another; he was chronically unsuited for most regular jobs. As a result, work providing cash money for his family was elusive, and when found, invariably transitory. Given his obstreperous nature, about the only viable work options involved cutting acid wood, gathering chestnuts for sale when they fell to the ground in incredible abundance in the fall, digging and drying wild herbs such as yellowroot for sale at a general store in the nearest town, and periodically earning a bit of cash through locating and robbing wild bee hives or selling molasses in the fall after the fall cane cutting and processing. Money changed hands when efforts of this sort came into play, but they were periodic at best and unpredictable. At the time most of the local economy operated on a barter system—the miller getting a portion of ground cornmeal; eggs being swapped for salt and other necessities that couldn’t be grown or harvested from nature; or some type of work being rewarded with clothing, shoes, or ammunition for hunting small game.

Such matters were well beyond the lad’s ken, although he did have a general if somewhat vague notion of the realities of daily life. He had no overweening wish for most material goods—desires of that sort don’t develop when there is a near total absence of luxury. But with Christmas approaching he did have a consuming desire for a single gift. Throughout the spring, summer, and fall his father had periodically let him use what most men of that era considered the ultimate tool–a pocket knife. The youngster’s apprenticeship with the knife involved practical matters such as cutting up seed potatoes for planting, suckering tomatoes, and whittling wooden pegs to hold barn doors in place. There had also been pure pleasures such as shaping a dogwood fork into a dandy slingshot and, with a bit of help, crafting a whammy diddle. His father had also demonstrated the proper use of a whetstone to keep the knife’s blades razor sharp while simultaneously emphasizing that it was a potentially dangerous tool. The boy had learned a hard lesson on that front when a bit of carelessness while whittling resulted in a deep cut to his left index finger.

With careful treatment from his mother, including application of some salve she made and keeping the digit wrapped in cotton cloth that had been boiled to sterilize it, the injury soon healed and was forgotten except for the lesson it offered. Once that episode was behind him, to the eager youngster’s great delight his father commented on more than one occasion: “First thing you know you’ll be ready for your own knife.” With those words firmly implanted in his youthful mind, he cautiously expressed his single wish for a Christmas gift—a pocket knife.

The youngster reckoned that reasonable. After all, he had no understanding that a decent two-bladed knife with brass bolsters and stag handles sold for a dollar or more. That was a significant amount of money in an area when a day’s wages might amount to no more than two dollars and in a family lacking predictable income. There may have been a hidden message in his sire’s muttered responses to the effect of “I don’t know, times are mighty hard,” but they went unrecognized and did little if anything to quell the boy’s desires. Even though he knew from previous Yuletide experiences not to expect too much, he took considerable comfort in the fact that his parents had not explicitly said “No.”

That formed the background to daylight on December 25, 1916. The family always rose with the chickens, and by cock crow on a bitterly cold morning the boy and his numerous siblings were up and about. They collectively rushed, half dressed, with tousled hair and eyes bright with anticipation, to the fireplace area of their simple log home. That was where their stockings, lovingly knitted by their mother, hung from the mantle. They knew nothing of wrapped presents or a Christmas tree—the Yuletide celebration was limited to good wishes, perhaps a bit better dinner fare than usual, and whatever the stockings contained. This year, as was the case every Yuletide, each stocking was well stuffed, but the contents were what previous Christmas experiences had led the children to expect—the stockings contained a single orange; a personal item in the form of mittens, scarves, or headwear made by their mother; a couple of apples from the family orchard; chestnuts and hazelnuts gathered nearby; and a few pieces of hard candy.

The starry-eyed boy immediately noticed, however, that right at the bottom of his stocking there was a tell-tale bulge in the shape of a pocket knife. Eagerly he dug through the fruit, nuts, and candy to reach that item, only to have unbridled excitement give way to abject dismay. It was indeed a pocket knife of sorts—a piece of hard candy shaped and colored to resemble the real thing. Heartbroken, he rushed from the room so no one would see tears rolling down his cheeks while biting his lip to keep from crying out loud in his anguish.

That bitterly disappointed little boy was my father. Yet to his lasting credit and as a testament to the toughness and resiliency of his character, the bitter dismay of that occasion did not result in lingering despondency. Instead, he managed to turn a moment of abject sadness into a lifetime fill with countless ones of enduring gladness.

First with his sons and subsequently with his grandsons, whenever Christmas rolled around Daddy made sure a knife of some type—initially a quality pocket knife with two or three blades, then later fixed-blade hunting or special-purpose knives—appeared under the tree or in our stockings. He continued this practice for virtually all of his 101 earthly years, and over the decades one of the highlights of our December family gatherings was hearing him relive that sorrowful yet shaping moment from his youth.

“I never want my offspring to be without a good knife,” he would say. “It’s a companion that will serve you well in some way, every day, for all your years.” Whenever one of us pulled out a pocket knife he had given us, Daddy’s eyes lit up with sheer joy. He took immense pride in the Eagle Scout rank attained by each of his grandsons and was delighted they had Boy Scout knives to complement those he had given them.

At his funeral service family members, male and female, all carried a knife he had given us or that came from his own sizeable collection. Afterwards, all who were physically able to do so bushwhacked to his long deserted boyhood home place a country mile from any trail. There we toasted his memory with pure, sweet water from the spring that once served the family.

As I joined this moving moment of farewell one hand lifted the tin cup filled with water to my lips while the other grasped a tangible link to the man– a pocket knife embodying his spirit and memory. I suspect others did the same.

JIM’S DOIN’S

Recent weeks have seen me perhaps a bit less productive on the writing front than usual, or at least that would seem to be the case if you measure matters in terms of recent publications. However, I am busy on two books that are under contract, and that’s taken up a goodly portion of my time. One, which will be co-authored with my brother, Don, is to be a volume in the massive “Images of America” series published by Arcadia. It will cover our home town, Bryson City, NC, and will focus on vintage images of the people and events in that little community in days of yesteryear. The second will be a sort of cookbook/storytelling combination somewhat in the vein of my culinary memoir, Fishing for Chickens: A Smokies Food Memoir. It will feature stories taken from food-focused newspaper columns of one of my favorite mountain writers from days gone by, John Parris, and pair them with recipes for the subjects of the columns. Tipper Pressley will be helping me out with supporting photographs and maybe some recipes.

I’m also excited to share news regarding a completed manuscript that carries the working title “Profiles in Mountain Character.” This collection of 36 vignettes of individuals representative of various aspects of mountain days and ways in the 19th and 20th century is in the hands of the University of Tennessee Press, and thanks to very positive reports from expert readers they had review the material, I’m quite hopeful that a contract offer will be forthcoming in the aftermath of their editorial board’s meeting next month.

My recent publications include, as usual, weekly columns in the Smoky Mountain Times and article publications. The latter include ”Remembering Mr. Buck,” “Sporting Classics Daily, Dec. 11, 2025; ”Merry Memories,” Columbia Metro, Dec., 2025, pp. 106-12; and “Indoor Winter Recreation in Days Gone By,” Carolina Mountain Life, Winter, 2025/26, pp. 69-70.

RECIPES

Since this month’s newsletter is Christmas themed, it seems appropriate to share some recipes that were a family tradition in the season. Looking back, I realize we ate mighty well, and these offerings, all focusing on the sweets, exemplify the kind of special treats enjoyed during Yuletide.

BLACK WALNUT BARS

CRUST

½ cup butter

½ cup packed brown sugar

1 cup flour

FILLING

1 cup brown sugar

2 eggs, beaten

¼ teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon vanilla

2 teaspoons flour

½ teaspoon baking powder

1½ cups shredded coconut

1 cup black walnut meats

Cream butter and brown sugar. Slowly add flour and mix until crumbly. Pat into 7- x 11-inch baking dish. Bake for 8-10 minutes at 350 degrees until nicely browned.

For the filling, combine brown sugar, eggs, salt, and vanilla. In a separate bowl, add flour and baking powder to coconut and walnuts. Blend into egg mixture and pour over baked crust. Return to oven and bake for an additional 15 to 20 minutes or until done. Cut into bars and place on wire racks to cool.

OATMEAL/CHOCOLATE CHIP/WALNUT COOKIES

1¼ cups softened butter

½ cup granulated sugar

¾ cup firmly packed light brown sugar

1 large egg

1 tablespoon vanilla extract

1½ cups all-purpose flour

1 teaspoon baking powder

½ teaspoon salt

3 cups quick-cooking oats

1 cup semisweet chocolate chips

¾ cup black walnuts, chopped and toasted

Beat butter at medium speed with a mixer until creamy and gradually add sugars, beating well. Add egg and vanilla, beating until combined. Mix flour, baking powder, and salt and then gradually add to the butter mixture, beating until blended. Stir in oats and remaining ingredients. Drop by rounded tablespoonfuls onto baking sheets. Bake at 375 degrees for 12 to 15 minutes or until lightly browned. Cool cookies on baking sheets for a minute and then remove to wire racks to cool completely.

SUPER EASY BLACK WALNUT FUDGE

Many fudge recipes are complex and time-consuming, but not this one.

12 ounces semi-sweet chocolate chips

1 can (14-ounce) sweet condensed milk

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

½ cup black walnut meats

Line a 9- x 9-inch baking pan with wax paper, completely covering the bottom and sides and have in readiness. Place the chocolate chips (they must be semi-sweet, not milk chocolate) and sweetened condensed milk in a large bowl and microwave for 1 minute. Stir, making sure the chips melt completely, and if necessary, microwave a bit more. The chocolate needs to be smooth. Immediately stir in the vanilla and walnut meats and then transfer to the lined pan. Spread evenly and place in the refrigerator for at least 2 hours to set. Remove the fudge and cut into small squares once it has set and then store in an air-tight container. It can be returned to the refrigerator or kept at room temperature. It will be softer if the latter approach is taken.

RUSSIAN TEA

At Christmas Momma always made a big batch, or maybe two or three of them, of this seasonal delight. It was served at family gatherings, to visitors who just happened to drop by, at

church functions, and just as a refreshing hot drink on a cold winter’s day.

½ teaspoon cloves

1 cup sugar

½ teaspoon cinnamon

1 gallon water

1 tall can orange juice concentrate

Extra sugar if desired

Bring these ingredients to a boil and continue for five minutes. Then add:

4 tea bags steeped in a pint of boiling water for five minutes.

¾ cup fresh lemon juice

1 tall can pineapple juice

1 quarter apple cider (optional)

1 ½ cup fresh orange juice

The quantities of juice can be varied if you prefer one taste to another. This recipe will make 20 generous helpings, and leftovers can be stored in the refrigerator and reheated as desired. Grandpa Joe would sasser a piping hot cup of this (he called it “Rooshian” tea), slurp with obvious delight, and declare, “My, that’s some kind of fine.”

ORANGE SLICE CAKE

I have no idea when the waxy, sugar crystal coated candy known as orange slices first came on the market, but it was available loose in jars (like peppermint sticks and a lot of other candy) from my earliest memories. At some point around 1950 someone in the family, quite possibly my Aunt Emma since I always associate this dessert specifically with her, obtained a recipe for a rich cake which incorporated orange slices into what was almost a fruit cake. Since it contained plenty of black walnuts, an ingredient almost sure to provide any dessert with a doctoral degree in deliciousness, it was a huge hit with me. This recipe is the one Mom used to make the cake.

1 cup butter

6 small, 5 medium, or 4 large eggs

2 cups sugar

1 teaspoon soda

½ cup buttermilk

3 brimming cups all-purpose flour

1 pound dates or yellow raisins, chopped

1 pound candy orange slices, chopped

2 cups black walnut meats

1 can flaked coconut or the equivalent in freshly grated coconut (the latter makes for a more moist cake)

1 cup fresh orange juice

2 cups powdered sugar

Cream butter or and granular sugar until smooth. Add eggs, one at a time, and beat well after each addition. Dissolve soda in buttermilk and add to creamed mixture. Place flour in large bowl and add dates, raisins, orange slices, and walnuts. Stir sufficiently to coat each piece.

Add flour mixture and coconut to creamed mixture. This makes a stiff dough that should be mixed with your hands (butter your hands or use rubberized cook’s gloves to avoid the batter sticking to your hands). Put in a greased and floured tube pan. Bake at 250 degrees for two and a half to three hours. Combine orange juice and powdered sugar and pour over hot cake as a topping and to make it moister. Allow to cool before serving.